You have your patented technology. You’ve demonstrated what that technology can do. You’ve spent millions placing steel in the ground to launch an operational plant for your product and commercialize your operation. Mission accomplished, right?

Not quite, says Mark Warner, the founder of Warner Advisors. During a packed presentation at this year’s InformEx in New Orleans, Warner laid out his “Top Ten Lessons Learned Commercializing Advanced Biotechnologies,” which gives tips for navigating all of the bumps that are likely to arise as you steer your company from bench-top operations to commercial operation.

Here’s a summary of what Warner says he’s learned after 30 years in the biz.

1. Build The Team

When putting together the team, it’s all about identifying the experience types needed to cover the host of new challenges that come with scaling up.

“No experience is good or bad,” Warner said. “Everyone has good experience and you just have to apply what you know.”

Most startups are R&D focused, but as the company begins to scale up, industry experience becomes more vital. Warner said it’s also important to admit when a team member isn’t a good fit for the rapidly changing process of commercialization.

2. Process Development

“It’s like having your kid playing on a soccer team,” Warner explained, using a metaphor for his second point. “Would you rather they won MVP or that the team won the championship?”

While startups are generally offering an in-demand compound more efficiently, sustainability and cost-effectively, they can also get tunnel vision with their technology. Instead of focusing on how to keep the core technology operational, Warner says companies need to remember that it is just one cog in a much bigger machine, so it’s important to make sure the entire process can run smoothly.

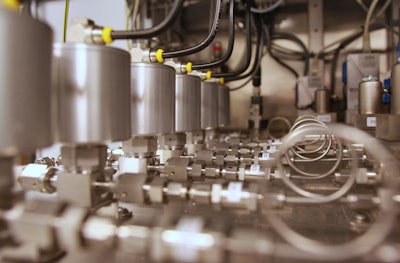

3. Facility Design

When it’s time to give your technology a home, Warner emphasized the need to recognize the difference in standards between industries. This can be especially important to keep in mind when shopping for equipment: Just because a piece of equipment is expensive and pharmaceutical grade, that doesn’t mean it will be the right fit in a food processing plant.

4. Scale Up

“Less than 10 percent of processes that work on a bench are commercially viable,” Warner said.

With that reality-check in mind, Warner said companies can often predict how well a technology will scale by running a fully integrated pilot process. How big should the pilot be?

“The jump in scale should not be greater than 10 times the capacity of the unit operations tested in the pilot,” Warner has written on the topic.

Warner also suggested that companies run the process long enough to understand the implications of handling the materials and how much waste it will create.

5. Integrating Unit Operations

As another example of why there’s no substitute for a fully integrated pilot process, Warner said he’s learned the hard way that you can’t always predict how a technology will work even if it’s been done many times in the past. Why? Even if the process has been tested with one material, even a very similar material (such as various kinds of oils, for example) can produce unpredictable outcomes and different contaminants.

6. Location, Location, Location

It might be tempting to head out of town to cheaper pastures, but Warner cautioned against choosing a location that could make it difficult to address arising problems. Rural locations, for example, can make it difficult to get to necessary resources, such as a place that can fix or replace broken equipment.

Setting up shop in foreign countries can also make it difficult to secure vendors and hire staff.

While predicting these challenges and hiring early and often can help make foreign ventures successful, Warner writes that he generally recommends targeting the U.S. for initial operations.

7. Regulations

“Some of the best money you can spend is for advice on regulations,” Warner said.

Even if your product is chemically identical to another product on the market, Warner says that it can still be regulated differently. Warner also cautioned that regulations don’t always follow common sense — making it difficult to predict how they can affect your process. And when it comes to regulations, you don’t want any surprises popping up as you scale your business.

8. Finances

Warner’s main financial message was, “The tail really does wag the dog.” Meaning: You have to know if the balance sheet is funded — whether it’s equity funding or a bank loan, for example — because it can have dramatic implications on how your project will be executed.

9. Facility Start Up

Don’t expect the process to move too quickly, Warner said. On average, he said it can take about six to 18 months for a facility to be built. Expect issues to arise, no matter how much you’ve tested your technology, and be prepared to make adjustments.

10. Plant Operations

“It’s not grad school,” Warner cautioned.

There can be challenges to the team culture during the scale-up phase. As mentioned, the right staff can make a huge difference in your company’s success, and it helps to remember the roles that everyone serves. Scientists, for example, are driven by their desire to discover. Process operators, by contrast, are focused on predictability and reliability. Warner has even explored this topic in an article called, “Engineers Are From Mars, Business Developers Are From Venus.” And by recognizing how both roles are valuable and critical for long-term success, you can help both sides work more harmoniously together.

Want to learn more? Check out Warner’s full-length article, “Top 10 Lessons Learned Commercializing Advanced Biotechnologies,” published on Biofuels Digest.