The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that toxic chemicals in public water systems across the U.S. were 24 times more prevalent than the Environmental Protection Agency had previously acknowledged.

EPA testing of the chemicals—perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, also known as PFAS—have been found in public water supplies in 33 U.S. states. Drinking water from California, New Jersey, North Carolina, Alabama, Florida, Pennsylvania, Ohio, New York, Georgia, Minnesota, Arizona, Massachusetts, and Illinois account for 75 percent of the unsafe supply described by the CDC.

There are about 3,500 different types of PFAS, and they have been in production since the 1940s. Some forms of the compounds are expected to remain intact for thousands of years, and they are often dumped into water, the air, and soil during production.

In the 1970s, DuPont and 3M used PFAS to develop Teflon and Scotchguard, which were then incorporated into everyday products, including gum wrappers, sofas, frying pans, and carpets, among many others. PFAS were also used frequently in the military in foam that snuffed out explosive oil and fuel fires.

It has been known that in certain concentrations, the chemicals could be toxic if people breathed dust or ate food that contained them. Scientific studies found a probable link between the chemicals and kidney and testicular cancer, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, hypertension in pregnant women, and high cholesterol, among other health risks.

While unsafe levels of PFAS can contaminate drinking water around military bases and factories, the EPA says 80 percent of human exposure to the chemical comes from consumer products in the home.

As the use of PFAS in production increased, the EPA began to investigate the chemical’s potential damage to human health and the environment in 2000. Blood tests of plant workers from DuPont and 3M became public, causing a growing concern about the health risks of the chemicals.

The EPA launched its first draft risk assessment for PFOA—one chemical in the PFAS family—by 2003. The assessment concluded that plant workers exposed to PFOA had a higher risk of dying of prostate cancer.

In 2009, the EPA issued provisional voluntary guidelines for safe levels of PFAS in drinking water. However, the agency didn’t mandate those limits, or create any regulation enforceable by law.

Other instances of water contamination across the U.S., notably in Minnesota and Alabama, led to heightened public concern. In response, the EPA decided to test for the chemicals in public drinking water systems, and began to reevaluate its 2009 guidelines.

In 2016, the agency announced a dramatically lower limit for how much PFAS exposure was considered acceptable. The new limit advised that no more than 70 parts per trillion of the chemicals was deemed safe—less than one-eighth the amount it had once said. The new limit is less than the size of a single drop in an Olympic pool.

Even though the EPA promoted this new standard, it remained a voluntary and unenforceable limit. PFAS were not classified as a hazardous substance, and therefore, the EPA couldn’t hold water utilities, companies, or any polluters accountable.

The Department of Defense also launched a full-scale review of PFAS contamination in water systems in 2016, despite the lack of clear regulatory limits from the EPA. It reported that 564 of the 2,445 off-base public and private drinking water systems that it had tested contained PFOS or PFOA above the EPA’s advisory limits. It also announced that a shocking 61 percent of groundwater wells tested exceeded the EPA’s threshold for safety.

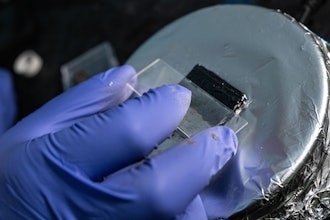

Both the EPA and the DOD chose not to use the most advanced tools for measuring or to gather the most comprehensive data on the contamination. While Method 537—a lab test used by scientists and regulators to achieve confident sampling results—has the ability to detect 14 PFAS compounds, the EPA only asked for data on six of them.

The agency also set detection thresholds for the six PFAS compounds as much as 16 times higher than what the test was sensitive enough to detect, so only the most extreme cases of contamination were reflected in the dataset.

In its water quality report, the EPA said that PFOA was detected in 1 percent of water samples across the U.S. However, when Eurofins Eaton Analytical—the largest drinking water test lab in the country—reanalyzed the data the EPA didn’t use, it discovered that the PFOA chemical was in almost 24 percent of the samples.

Another chemical component of contamination—PFBS—was found in less than one-tenth of 1 percent of all water samples, according to the EPA. Eurofins Eaton Analytical’s re-analysis found the chemical in nearly one out of eight samples.

Despite these findings, the EPA defended its testing protocol, saying its testing is designed to yield consistent, reliable results even if labs conducting the tests are less sophisticated.

In early 2018, the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR)—a branch of the CDC—launched a nationwide health study on the PFAS water contamination crisis. The study’s results showed that the chemicals endanger human health at far greater levels than the EPA had previously predicted. For the chemical PFOA, the ATSDR exposure limit was seven times stricter than what the EPA said was safe. For the chemical PFOS, the ATSDR limit was 10 times stricter.

In May, the EPA and the White House pressured the ATSDR to withhold the health study from the public. According to internal EPA emails published by Politico, the agency feared a “public relations nightmare” if they had to explain the wide difference between the standards in the ATSDR report (at that time unpublished) and the EPA levels.

The ATSDR fell under pressure by over 53 public interest groups to release the study, arguing that the public needed to be aware of the toxic chemical crisis. State lawmakers complained of “a lack of urgency and incompetency” on the part of the EPA.

The Environmental Working Group—an advocacy organization whose scientists have studied PFAS pollution—said the ATSDR report shows that the EPA guidelines “woefully underestimate” the chemicals’ risk to human health. They estimate that at least 110 million Americans are at risk of being exposed to PFAS chemicals.

In response to the release of the ATSDR study, then-EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt said in a written statement, “The EPA will take concrete actions to ensure PFAS are thoroughly addressed and all Americans have access to clean and safe drinking water.”

The PFAS water contamination is now considered a national priority to the EPA. The agency says it will prepare a national management plan for the compounds by the end of the year. But Peter Grevatt, director of the agency’s Office of Ground Water and Drinking Water, said that there’s no deadline for a decision on possible regulatory actions.