Between 1962 and 1971, American C-123 planes doused Southeast Asian jungles with more than 19 million gallons of herbicide combinations as part of Operation Ranch Hand, an effort to wipe out vegetation that provided cover to enemy forces.

Now a generation of American service personnel continues to deal with the effects of Agent Orange more than 40 years after the military ceased spraying the powerful herbicide during the Vietnam War. According to a recent federal report, military personnel working on Vietnam-era aircraft years after that campaign ended may have been exposed to dangerous levels of the harmful chemicals.

Agent Orange, the most common of those “rainbow” herbicide combinations, has been linked to a litany of health concerns in subsequent years. It contains the dioxin TCDD, classified as a carcinogen by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Seven companies that manufactured Agent Orange for the military settled a class action lawsuit in 1984, and legal actions continued long after that $180 million victims compensation fund closed in 1997.

In 1972, following their missions in Vietnam, 24 of the C-123 planes were added to the Air Force Reserve for transportation and airlift purposes. An estimated 1,500 to 2,100 reservists trained and worked aboard those planes over the next decade.

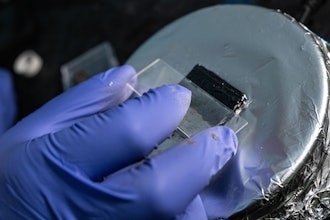

A panel convened by the Institute of Medicine found air and surface samples taken from C-123 aircraft between 1979 and 2009 had chemical levels at or exceeding cautionary standards, despite those samples coming years after the personnel had worked aboard the airplanes.

"Detection of TCDD so long after the Air Force reservists worked in the aircraft means that the levels at the time of their exposure would have been at least as high as the taken measurements, and quite possibly, considerably higher," said Robert Herrick, a senior lecturer at the Harvard School of Public Health and the committee chairman.

Some of those reserve members had applied for coverage under the federal Agent Orange Act of 1991, which covers for health conditions stemming from service-related exposure to the herbicide during the Vietnam War.

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, however, denied those applications after determining the reservists' service did not apply under the law. After a veterans group sought to reverse that decision, the VA asked the IOM to evaluate the plausibility of reservists' exposure to chemicals in Agent Orange.

The report says although some of the veterans “could have experienced adverse health effects,” it was impossible to determine their exact exposure due to limited sampling data and work records.