HIGHLANDS, Texas (AP) — Jackie Young clutched the government's latest report on the health effects of decades of dioxin contamination in the San Jacinto River at a community meeting on Wednesday night,  frowning slightly.

frowning slightly.

"We've been begging the EPA for years to study our health," said Young, an environmental advocate who organized the meeting.

The Houston Chronicle reports she told the crowd it was easy to find "tragic stories" in this small town in eastern Harris County near the San Jacinto Waste Pits Superfund site.

"I'd been warned by health experts that we may be disappointed by the outcome of the government's study," she told the crowd.

She'd hoped the experts were wrong, and those hopes were buoyed in January by an email from a state health official. A cancer cluster investigation had found elevations of childhood eye and brain stem cancer of a "sufficient magnitude to warrant further investigation," a lead epidemiologist wrote.

But that cancer cluster investigation still has not been published.

And the most recent government report, the one Young clutched in her hand, said a more in-depth, community-wide health study "is not recommended."

"Our health deserves to be truly investigated," she said.

Heads bobbed silently again.

But there was no one from the government there to see them.

A Department of State Health Services spokesman said the cluster report is under review and will be released once it is finalized. It will quantify the cancer cases and make recommendations about further study. But it won't examine the potential causes.

Each year, state and local officials across the United States receive about 1,000 reports of potential cancer clusters. Most are based in perception rather than fact, experts say. Someone gets cancer, or a loved one gets cancer, and then people start talking about other neighbors with cancer.

That started years ago in Highlands, a town of 7,000 that sits above the eastern bank of the San Jacinto River. Most of the talk focused on the children. Brandi Gonzalez's daughter, Maycie, is one of the kids they whisper about. When Maycie was a baby, her mother noticed a white glare in her eye one night in the bathtub. "It just seemed like one of her eyes was empty to me," she said.

At 11 months, Maycie was diagnosed with retinoblastoma, an eye cancer identified in only about 250 to 350 children in the United States per year. The doctors told Gonzalez that Maycie had a heritable form of the cancer, but she and her husband couldn't trace it in their families, going back generations.

Maycie lost one eye to the cancer right away.

"For a year and a half," Gonzalez said, "we tried to save the other eye."

Gonzalez said she heard about two more children in town with retinoblastoma. One, she said, was related to the Episcopal minister on Main Street. She couldn't recall much of anything about the other child.

But she remembers Hannah Harpster. Maycie's friend at day care, Hannah was diagnosed at age 5 with a rare and aggressive brain tumor.

When Hannah was in the hospital, the father of a boy from Crosby, about six miles away, stopped by the hospital and said his son had died of the same cancer, Hannah's grandmother recalled. Toward the end, Hannah could only move her eyes. Her obituary said she "peacefully climbed into the lap of our Lord."

Two months after Hannah died, in 2005, Texas Park and Wildlife Department officials discovered the waste pits.

By 2008, it was on the federal Superfund list. The EPA report said tugboats pushed barges of waste sludge from Champion Paper Co. in Pasadena to three pits for offloading and storage in the 1960s. The EPA listed hazardous substances found in the pits, including elevated levels of polychlorinated dibenzodioxins (PCDDs) and polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs), commonly known as dioxins and furans. Dioxins are considered carcinogens by the World Health Organization and have been linked with a battery of other potential health effects, including birth defects.

Some samples taken at the site were 680 times higher than the government's screening levels for dioxins in residential soil.

The chemicals had seeped into the river as the pits subsided over the years and the currents eroded the outer berm.

Signs and fences went up along the river's western bank, near the Interstate 10 overpass between Channelview and Highlands.

Don't swim, the signs warned. Don't eat the fish.

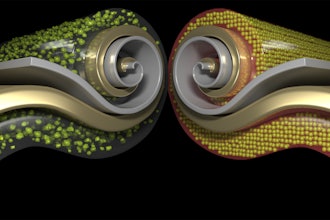

In 2011, the pits were covered with "armored caps" — layers of geomembrane topped with tons of stone — to stop the dioxins from spreading.

Around that time, Young, who grew up two miles from the pits, started going door-to-door in Highlands as part of a project for her environmental management class at the University of Houston-Clear Lake. She regularly had seizures and wore wrist braces for tremors and nerve pain. Her stepfather, a car hauler, had multiple myeloma. He also had chloracne, she said, which is associated with dioxin exposure. Her dog died of cancer.

As she knocked on doors, she said, she heard similar stories.

What, she wanted to know, is "making everyone so sick?"

Arnold Schecter, a retired professor of environmental and occupational health sciences at the University of Texas School of Public Health, is a leading national expert on dioxins. He said they can cause certain types of cancer such as soft-tissue sarcoma and Hodgkin's lymphoma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Schecter said a quick search of scientific journals found no evidence of an established link between childhood retinoblastoma or glioma and dioxins.

Still, he added, dioxins can promote the growth of cancers initiated by other chemicals, creating a kind of synergistic effect. It is the same kind of effect seen in uranium miners who smoke, he explained. Exposure to the combination of uranium and cigarettes creates a greater risk of lung cancer than exposure to either factor alone.

The state and the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry published a health assessment in 2012 that examined the cancer risk posed by the waste pits. Living near the pits "has no bearing on cancer risks or other negative health impacts," unless people also engage in "risky behaviors." Those behaviors include regularly touching the site's soil or eating fish or crabs from the river or ship channel.

Young questioned whether the exposure scenarios in the report were realistic. What about the decades of past exposure, she said, when the dioxins seeped into the river and migrated from the site? She started pushing for a cancer cluster investigation.

But a "cluster" has different meanings: one for the public, and one for epidemiologists.

The movie "Erin Brockovich" often is cited by scientists as the popular perception of a cancer cluster. Chemicals are discovered in the groundwater or the soil, and the contaminants are blamed for causing cancer.

Scientists define a cluster as a greater than expected number of a certain cancer in a particular geographic area during a set period of time.

During the past 40 years, state and federal officials across the United States have investigated thousands of possible neighborhood cancer clusters.

Only a handful have pointed to a specific environmental exposure, and even then, often tenuously.

More than 260 times since 2004, DSHS epidemiologists published cancer cluster investigations. In the majority of cases, the state found no excess of cancer. In 72 of the reports, they identified statistically significant elevations, mostly involving common cancers, like lung, prostate and breast.

"We do not know why," the state's epidemiologists wrote again and again. "We may never know why ."

None of those reports of elevated cancer incidences prompted the state to take the next step — examining the feasibility of an epidemiologic study, officials said.

Still, the state frequently contributes not only data but also expertise to major cancer research projects in partnership with universities and the federal government, said Melanie Williams, DSHS' branch manager for the Texas Cancer Registry. One example, she said, is a 2007 study that identified a possible link between childhood leukemia risks and proximity to the Houston Ship Channel.

In 2001, lawmakers created the Texas Environmental Health Institute in response to citizen concerns about the impact of pollution. The partnership between DSHS and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality was intended to examine how to reduce health problems associated with contamination.

But the institute received no funding this year.

"It's always a matter of money," said Kathleen Garland, an environmental management expert with the University of Houston-Clear Lake who has researched the waste pits as a consultant for Young's organization. Even in-depth studies often don't yield results, she added.

"With the slow onset diseases like cancer, it is very hard to link cause and effect," she said.

Even if a cancer is linked to a particular toxin, there is the question of where the contamination came from. Eastern Harris County is dotted with Superfund sites, chemical plants and barge-cleaning companies.

There is one more reason, Garland said, that in-depth health studies are rare.

"Frankly," she said, "the industry has been very good at defending against them."

Lawyers for International Paper Company, McGinnes Industrial Maintenance Corp. and Waste Management Inc. declined comment or did not return phone calls on Friday.

More than 170 people in Highlands and Channelview — including Young and the families of Maycie Gonzalez and Hannah Harpster — have joined a civil lawsuit against the companies, said attorney Fletcher Cockrell.

Fishermen who lived for decades off their catch in the river and Galveston Bay also have sued.

Harris County won a $29.2 million settlement in November from two of the companies for violations of environmental laws. The county is appealing a jury verdict won by International Paper in the lawsuit.

The county is lobbying the EPA to force the companies to clean up the waste pits rather than just containing the chemicals under the caps.

Gary Miller, the EPA's Superfund remedial project manager for the site, said this week that the agency is waiting for a report by the Army Corps of Engineers before recommending the best clean-up option. The EPA plans to hold another public meeting soon, he said.

"As long as these toxins sit here, the community is going to continue to live in fear," Young said, "and the risk is still there, sitting under a pile of rocks."

The companies have suggested capping the pits is enough to protect the public. Estimates to fully remove the contaminants from a portion of the site start at about $104 million.

"People's lives aren't worth that much?" Brandi Gonzalez asked. "It's frustrating."