Shahid Abdullah has been in business long enough to spot a good opportunity. Abdullah is the president of the Sapphire Group, one of Pakistan’s largest textile companies with 16,000 employees, $800 million in annual revenues, and a global base of customers. But when his country started running out of electricity a decade ago, he switched gears and built a large power plant in Muridke, just north of Pakistan’s second largest city Lahore. “Moving into power generation was a step that made sense,” he says. “Not just from a business perspective, but also in terms of realizing our mission and contributing to the development of the communities in which we work and live.”

Abdullah’s calculation was simple. Lack of power is one of Pakistan’s burning needs. Electricity consumption is growing by close to 8 percent, and peak power demand exceeds supply by more than 4 gigawatts (GW), a massive amount. But his journey was far from easy.

The Muridke Power Plant generates 234 megawatts (MW), but from the start in 2010 it grappled with fluctuating fuel costs, which make up some 85 percent of its operating expenses. Fuel savings of just 1 percent could boost its net income by as much as 20 percent, but the downside was equally steep.

Abdullah started looking for a solution and learned about the Industrial Internet, a digital network connecting, collecting and analyzing data from sensors installed inside machines, including turbines that produce electricity. “His answer was in numbers,” says Azeez Mohammed, president and CEO of GE Power Generation Services in the Middle East and Africa, who started talking to Abdullah in 2014.

Mohammed proposed to embed hundreds of sensors and other digital instruments in Abdullah’s turbines, analyze the data they collect, and use the information to improve the plant’s performance, optimize production and reduce unplanned downtime. But Abdullah was cautious. “The last thing I wanted was to be a guinea pig in GE’s ‘first-of-its-kind’ experiment,” he laughs.

GE’s Mohammed, however, was convinced that the project would work. So much so that he proposed Abdullah a deal: GE would pay for the sensors and the software and then split all benefits with Sapphire under a win-win scenario.

With Abdullah on board, GE dispatched a team of technicians and software engineers to Muridke. They spent a month developing a self-learning analytical model based on huge amounts of data from the gas turbines and other plant assets at Sapphire. The model allowed them to predict changes in efficiency, electricity output and other outcomes under different production scenarios without having to make any changes to the equipment itself.

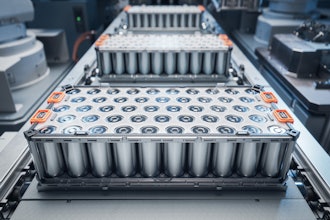

In October 2014 the team connected the system to the plant’s two GE 6FA gas turbines, which GE engineers specifically designed with the Industrial Internet in mind. By December that year, the Sapphire plant has started seeing the benefits.

The heart of the system is GE’s Predix software platform and an advanced analytics application called Asset Performance Management (APM). The app allows industrial assets talk seamlessly with each other in a secure manner, and uses analytics to make the equipment more efficient.

The GE team is now working to link power plant’s steam turbine to system. The software is so versatile it doesn’t mind that turbine was the Czech industrial company Skoda, not GE.

GE estimates the Industrial Internet could bring the Muridke Power Plant millions of dollars in benefits over the next decade.

Others in Pakistan will benefit from the system as well. Electricity shortages, known locally as ‘load-shedding’, are an everyday reality that families and businesses have had to learn to cope with them. “Our entire daily routine, from the time we sit down to help our children with their homework to the time we iron our clothes, is determined by the load-shedding schedule,” says Zeba Zahid, a mother of three and resident of Lahore, one of the cities that benefits from the power produced at the Muridke Power Plant. “It’s especially difficult to deal with in the summer, when peak temperatures cross 45 degrees Celsius [113 Fahrenheit] and load-shedding often exceeds 12 hours a day.”

GE estimates that making Pakistan’s power plants smarter with data analytics and software could add 600 megawatts to the country’s power output without building a single new plant. That’s comparable to building an entirely new power plant.

Abdullah feels that he made a smart choice. “As far as I’m concerned, the benefits offered by Industrial Internet based solutions are real and immediate,” he says. “This is an opportunity that Sapphire and Pakistan cannot afford to miss out on.”

For more stories like this, visit GE Reports.