PITTSBURGH (AP) — The U.S. Coast Guard wants to allow barges filled with fracking wastewater to ply the nation's rivers on their way toward disposal. Many environmentalists are horrified, but industry groups say barge transport has its advantages.

Now, the wastewater is usually disposed of by truck or rail, which poses more risk for accidents than shipping by barge, according to a government report. And one barge can carry about the same amount of waste as 100 exhaust-spewing trucks.

The disagreements go to the core of the fight over shale gas drilling. Environmentalists say the chemicals in fracking waste are a tragedy in the making, but the industry says far greater amounts of toxic chemicals are already being moved by barge, including waste from oil drilling.

In 2010, U.S. barges carried 2,000 tons of radioactive waste, almost 1.6 million tons of sulfuric acid and 315 million tons of petroleum products, according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

"We expect that shale gas wastewater can be transported just as safely," said Jennifer Carpenter, of American Waterways Operators, a trade group based in Washington, D.C.

Environment America, a federation of 29 state-based groups, strongly disagrees. The group said in a statement that it gathered 29,000 comments opposed to the proposal from people around the country. Courtney Abrams, the clean water program director for the group, urged the Coast Guard to "reject this outrageous proposal."

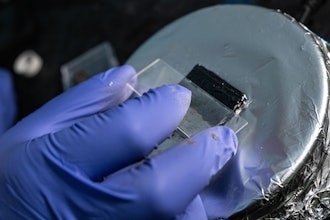

Extracting natural gas trapped in shale formations requires pumping hundreds of thousands of gallons of water, sand and chemicals into the ground to break apart rock and free the gas. Some of that water, along with large quantities of existing underground water, returns to the surface, and it can contain high levels of salt, drilling chemicals, heavy metals and naturally occurring low-level radiation.

The Marcellus Shale formation, underlying large parts of Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio and some neighboring states, is the nation's most productive natural gas field. Thousands of new wells have been drilled there since 2008, and hundreds of millions of gallons of wastewater needs to be disposed of each year.

Some states, such as Texas and Ohio, have many underground waste disposal wells. But Pennsylvania has only a few, meaning the leftovers have to be shipped elsewhere.

The Coast Guard proposal says barge companies want to move waste from the Marcellus region "via inland waterways to storage or reprocessing centers and final disposal sites in Ohio, Texas, and Louisiana." That means large quantities of waste could be shipped on major rivers such as the Ohio; one of its main tributaries, the Monongahela; and the Mississippi.

Critics say that if there were an accident, it could threaten the drinking water supply of millions of people. They also cite the uncertainty around what's in that toxic mix. The Coast Guard is proposing to address that by requiring chemical testing of each barge load before shipment; test results would also be kept on file for two years.

A Marcellus wastewater spill wouldn't be any different from other threats, said Jerry Schulte, the emergency response manager for the Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission, which has members in eight states. Occasional spills and other pollution are "a part of life" on industrialized waterways such as the Ohio, he said.

"Things happen, whether it's naturally occurring, or spills," he said.

Municipal water suppliers also monitor river water, and if there's a spill nearby, they shut intake valves until the problem has passed downriver.

One of the largest river spills in the region's history took place in 1988, when an on-shore storage tank ruptured in Pittsburgh, spilling about a million gallons of fuel oil into the river. The sludge flowed down the Ohio River, forcing many water suppliers to shut intakes for a week.

But according to a 2011 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, the fatality, injury and air pollution rates for barge transportation are far lower than truck or rail transport.

The Coast Guard is reviewing the comments from both sides, and it has the authority to approve or modify the rule. But there is no timeline for a decision, spokesman Carlos Diaz said.

A leading industry group supports using barges for the waste but isn't happy with the details of the Coast Guard proposal. In a Dec. 6 letter, the Marcellus Shale Coalition hailed the potential to reduce the waste being transported by highway but complained the proposal set the threshold too low for naturally occurring radiation, which would effectively prevent wastewater from being shipped by barge.

A spokeswoman for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency couldn't immediately say Friday whether they have a position on the barge wastewater issue.