There is a growing trend in manufacturing: energy recycling. More and more companies are using processing byproducts and waste to fuel their operations, creating cleaner, more efficient plants with lower energy costs.

Ethanol has garnered much attention in recent years, but when folks today speak of “ethanol” they are most likely talking about a corn-based product. Ethanol can come from a variety of places, however, ranging from municipal and industrial waste to agricultural and forestry sources. And those leftovers, known as “biomass,” are the basis for cellulosic ethanol.

Of course, the potential to generate energy from waste rather than food sources – not to mention oil - has both environmental and industrial benefits.

According to Bill Baum, executive vice president, business development at Diversa, a specialty enzyme optimization company, cellulosic ethanol can be made from sources like grain crops, switch grass, corn stalks, wheat straw, rice straw, grass clippings and wood residues - materials that are less expensive than corn and are not needed for other products. And for manufacturers, it has additional bonuses.

“In addition to fuel, cellulosic biomass can be converted into chemicals used to manufacture products that would otherwise be made from hydrocarbon-based petrochemicals, such as plastics, adhesives and paints,” Baum notes.

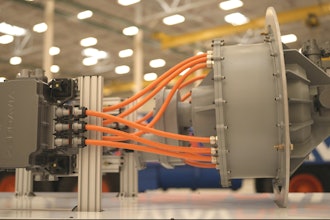

Another big manufacturing plus for cellulosic ethanol is that it can use waste from other processes to make fuel. Dr. Andrew Richard, CTO of Mascoma, a developer of bio and process technology for conversion of cellulosic biomass, said that facilities for producing cellulosic ethanol can be attached to other existing plants, such as those that manufacture paper, and use their waste to produce energy. Moreover, that modular style of addition could take advantage of today’s technology to make energy for tomorrow.

While it uses a less expensive feedstock than corn-based ethanol, production costs still need to come down. Cellulosic ethanol requires an additional pretreating step that corn-based ethanol doesn’t. In order to break down the chemical composition of the cellulose, it needs to be exposed to moisture, temperature or acid before it can go through fermentation and be turned into ethanol.

While it should be available on a commercial scale in about 6 years, perhaps sooner, some companies already have plans for the energy source.

FuelCell Energy Inc., which builds electric power plants for commercial and industrial customers, will provide an ultra-clean power plant in California’s San Joaquin Valley, which will run on fuel from dairy-processing waste and generate electricity to run a municipal wastewater treatment plant.

Another facility in Sierra Nevada will run a brewery power plant by using the methane byproduct of the brewery process, generating a cleaner, more efficient process. In California, FuelCell uses biogas from onion peel waste to generate electricity for a grower and processor of onions.

At Penn State University, researchers under Bruce Logan, Professor of Environmental Engineering, have taken wastewater from a Pennsylvania confectioner, apple processor, and potato chip maker and turned it into hydrogen gas.

Logan has also been involved in research involving the use of corn stover, or the part of the stalk that remains after the corn has been harvested, for ethanol production. Nearly 90 percent of the stover is left in the fields, and 70 percent of those stovers are cellulose or hemicellulose, which can provide energy.

“These studies demonstrate that there is great potential for electricity generation using corn stover biomass. Such energy production could be important as a result of the large amount of this material generated, estimated to be 150 million tons per year,” said Logan. However, large scale systems haven’t been built yet.

Meanwhile, in Vermont, instead of offering horse power they provide “Cow Power.” Central Vermont Public Service (CVPS) has the honor of being the state’s only direct farm-to-consumer renewable energy program. Anaerobic digesters, which are basically systems designed to treat waste and produce biogas, collect the methane from cow manure and turn it into energy.

There are similar anaerobic digesters at work with Intrepid Technology and Resources at Whitesides Dairy in Idaho and a cow biomass-powered fuel ethanol refinery from Hanes and Boone at Panda Energy International Inc. in Texas.

The U.S. is being joined by countries around the world seeking to lower emissions and dependence on oil. In Spain, Bio Fuel Systems has developed a process in which plankton is used for energy. New Zealand has its own processes using particular types of plants, namely a shrubby willow, and Brazil has been using sugar cane.

Cellulosic biomass is “the most undervalued and underutilized energy asset on the planet,” Baum said.

For more information on the Governors’ Ethanol Coalition, click here.

To comment on this story email us at [email protected].