Saanya Sethi

Saanya Sethi Nathan Wagner

Nathan Wagner  Robert Giacobbe

Robert GiacobbeMost people do not think about the complex orchestration that went into designing and manufacturing an airplane when they’re flying on one. The immense number of parts, technical content, third party coordination, and labor that helped crank out the final product is rarely top of mind for the air traveler. For the manufacturer, on the other hand, on top of flawlessly executing these processes they must properly execute their competitive strategy so they achieve their performance targets. It’s a vexing thought to juggle so many balls at one time.

This is where Business Architecture (BA) – often used interchangeably with Enterprise Architecture (EA) – plays a critical role: it enables a company, like an aircraft OEM, to decompose its competitive strategy, translate that into specific operating requirements, and then embed those requirements into the process, data and technology architecture of the organization. This approach enables the strategic alignment up and down the organization that so many businesses struggle to achieve. Suddenly juggling so many balls at once got easier.

This alignment – rarely found among large, multi-country, multi-BU corporations – provides competitive advantage where “strategy through execution” enables a company to be faster, and more agile, all while still managing its cost to serve. As the COO of a fast food chain once said, “I want to see a chicken killed each time I hear the cash register ring.” This somewhat exaggerated vision of strategic alignment is the centerpiece of BA.

The primary benefit of BA is that it enables a company to justify, implement and sustain the critical capabilities that aid in executing the competitive strategy. Examples of such critical capabilities would include smart factory, control tower, tooling optimization, or predictive maintenance, to name but a few. An effective BA program starts with defining a company’s competitive positioning. Common models for this include operational effectiveness (OE), product leadership (PL) or customer intimacy (CI).

That clearly-defined positioning will specify the relevant set of differentiating capabilities that the business must excel at to beat its competitors, create value for customers, and to win in the marketplace. And accordingly, those differentiating capabilities are the platform upon which the rest of the architecture will be built with a heavy emphasis on IT systems. These are the first stitches that will end up being the knitted fabric that creates the much sought-after strategic alignment.

For example, a CI-focused manufacturer will maximize customer fill rates as a critical key performance indicator. Understanding that the arrival of components to the assembly plant in synchronization with the master schedule is key to hitting customer due dates, the company implements a control tower to enable supplier visibility and inbound tracking.

Through a business architecture program, an operational value stream (OVS) is created such as “perform inbound materials management” that allows the control tower components to be implemented, managed and improved over their lifecycle. This OVS does, in part, enable the control tower elements and give it the right integration. In the BA world, this OVS can now become its own entity, providing benefits to the enterprise such as:

- It can be connected to other OVSs up- or down-stream, such as supplier source-to-pay enabling horizontal integration

- It can be connected to the lower-level process architecture called cross-functional processes (CFPs), enabling vertical integration

- Its own data requirements and information products can be documented and managed

- It can have modular, repeatable business services embedded in it such as a pricing or accounts payable function

...thus achieving the goal of developing a purposeful, integrated enterprise structure. Additionally, the “containerization” of value streams that BA relies on will also enable other benefits. One, it provides a clean approach to executive ownership of that OVS and its related capabilities. Two, it simplifies the sustainment of that value stream over time, as the organization can clearly see when it’s time to upgrade the technology, data, and organization elements. And three, it provides the basis for aligning systems and software to specific processes to ensure correct mapping.

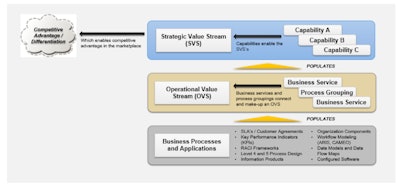

Figure 1 shows a common structure and hierarchy of a BA framework. This is just one possible variant, and searching the internet will demonstrate the hundreds of other examples that companies have used to define their business architecture. But even with this large variation, there is much commonality across all these different frameworks.

As Figure 1 shows, we have defined five major components that comprise our BA framework:

- Strategic value streams (SVS) – high-level activities that are directly linked to the firm’s competitive strategy that create value when executed. An example would be “Ideation to Build” or “Recruit to Retire.”

- Operational value streams (OVS) – operations-level activities that are connected together that directly support SVSs and create value when executed. An example would be “Order to Cash” or “Source to Pay.”

- Business capabilities – a collection of process, org, data and technology components that come together in a packaged way to deliver functionality in a specific functional space. An example would be “master production scheduling” or “integrated demand planning.”

- Business services – a collection of activities that are packaged together to provide a repeatable, commoditized service to consistently deliver an outcome at a defined service level. An example would be a financial analysis or a time-keeping function for payroll.

- Cross-functional processes – these are the traditional business processes that flow down from the OVSs into process levels 4 through 5 and directly support the OVSs when executed. An example would be “load demand history into forecast software” or “deliver parts to assembly position on shop floor.”

We’ll use the rest of this article to explain a real example of a large-scale BA design and deployment to bring the concept to life.

A global heavy equipment OEM (mining and construction equipment) embarked on a large, multi-tower program to replace several enterprise systems with engineering, fabrication and assembly operations at the center. The company defined the top-tier architecture with eight strategic value streams (SVSs) such as “strategically manage the customer lifecycle” and connected those to fifty+ operational value streams (OVSs) which resided one level down in the hierarchy. One example of an OVS was “conduct customer segmentation.”

This OEM’s competitive positioning was to present itself in the market as a Customer Intimacy business (e.g., maximizing customer service) with industry-parity capabilities in Operational Excellence. In other words, it was going to win and keep customers primarily based on service – accurate due date quoting, order fill rate, response to order changes – while still maintaining a competitive cost position with its peers.

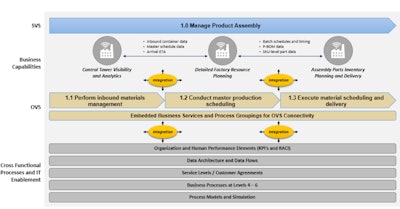

Deeper analysis of their strategy identified a number of differentiating operational capabilities that the OEM must execute well to be successful. Three we will highlight included control tower visibility and analytics; detailed factory resource planning; and assembly parts inventory planning and execution.

The first step was for the team to develop the relevant set of OVSs that covered the scope of product fabrication, assembly and integration. These included OVSs such as “Dispatch Tooling and Production Support Equipment”, “Consume Materials into Work Center,” and “Perform Readiness for Field Operations” to name just a few.

Second, a team of business architects and functional representatives developed the third level in the architecture called “cross functional processes,” or CFP’s. This activity was guided by a set of business requirements defined earlier, but also by the deep, specialized knowledge brought by the business architects on the team. These CFP’s that were designed would be classified as level four and five in traditional business process design, and they stretched across functional areas as needed.

Generally speaking, the development of the CFPs would not be configuration-level process development that supports system design and testing such as level 6 processes. That level of detailed solution development typically happens in the next project phase called “detailed design.”

Along the way the BA team built the associated work products to support the completed architecture, which included information products (e.g., defined master and transactional data entities), data flows, actors (e.g., roles for human resources) and key performance metrics. The consolidated set of these work products and CFP’s comprise the entire business architecture that defines the plumbing of an OVS, which in turns provides the superstructure to support one or more SVSs.

This cascading, linked hierarchy is the structure that enables strategic alignment. And now the organization has a platform which can be “consumed” – or integrated with – the new IT system as it is designed, configured, tested and deployed. The Systems Integration team now has a stable, defined and purposeful platform to work with when configuring their software.

Figure 2 provides a slice of how the combined business architecture appears as a final product for the example we’ve presented here.

For those of us who work in the business architecture space, there is an old saying: “If you don’t design your architecture, it will design itself.” And this is not a good thing. This is readily apparent from the many examples of IT systems and business capabilities that were implemented but did not help a company better execute its competitive strategy.

And we hope our message is clear: you can indeed avoid this trap by designing the architecture yourself, using a purposeful, methodological approach that begins by linking to competitive strategy and driving that requirement down to low-level solution functionality.

Nathan, Saanya and Robert a part of PwC’s Advisory practice. They can be reached at: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]