NEW YORK (AP) — There are three jobs open at Rodon Group, a plastic parts manufacturer near Philadelphia. But despite the reports of a shortage of skilled workers nationwide, CEO Michael Araten isn't sweating it.

Rodon, located in Hatfield, Pa., works with local community colleges to make sure students — the firm's prospective employees — get the skills they need to work at the company making plastic parts for products such as bed frames and machinery. Anyone using its manufacturing equipment needs to have math and computer skills.

"We're willing to look at non-traditional methods," Araten says.

Companies across the country have been working short-handed because it's hard to find workers with the skills they need. The shortage is harder for small businesses than it is for larger ones. They don't have as many employees to step in to when there's an opening. Twenty-one percent of the owners who recently took part in a survey by the National Federation of Independent Business said they had openings they couldn't fill.

But some owners are finding solutions. Like Araten, they partner with schools. Some are running in-house training programs or pair skilled employees with co-workers who aren't up on the latest technology. And others are changing their recruiting strategy.

The skilled-worker deficit is getting more attention as the economy improves and businesses hire more. President Barack Obama mentioned the issue in his State of the Union address last month, calling for more training for workers.

_____

THE PARTNERSHIP SOLUTION

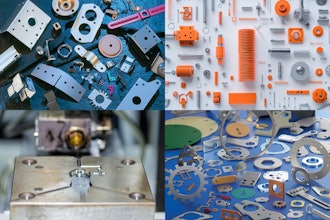

Araten and other Philadelphia-area manufacturers have formed a group to work with local community colleges to be sure students get the ground in math, science and computer skills that they'll need for jobs like building and operating robots. When they arrive at Rodon, they'll start learning the company's manufacturing processes. Rodon, which also makes K'Nex toys, brightly colored plastic pieces that can be combined to form cars, animals, rollercoasters and other objects, uses a manufacturing process called plastic injection molding that's run with computers and robots.

Rodon's workforce of about 100 is getting older. CEO Araten wants to be sure he has people ready to step in as workers in their 50s and 60s start to retire.

"That's why we've increased our relationship with schools to be sure we're first in line," he says.

Tailored Label Products' partner is a program called Second Chance, which finds training and jobs for students who are in danger of dropping out of high school, says Tracy Tenpenny, a vice president at the Menomonee Falls, Wis. company. The students learn how to use complex computer-operated machines to create customized labels that go into car engines and electronic equipment. They spend two hours each day in class and six hours at the factory earning slightly above minimum wage.

Tailored Label turned to Second Chance as the company started to grow and needed more skilled workers. The company has tripled in size over the last seven years.

"It's not easy finding people who are going to fit," Tenpenny says. "We needed someone who was able to handle a computer and utilize a digital die cutter."

Some of the students leave the company after they graduate. Tailored Label has hired several, and is paying for one of them to get his associate's degree in technical manufacturing at a nearby community college.

_____

A GROWING CONCERN

Most of the headlines about the skilled-worker shortage have focused on manufacturing. But it also affects companies that offer services — marketing and construction firms, for example.

Estimates of how big the shortage is vary. The consulting firm Deloitte said in 2011 that 600,000 manufacturing jobs were unfilled at companies of all sizes because employers couldn't find workers with the right skills. Deloitte based that number on a survey it conducted with the Manufacturing Institute, an organization that researches issues in manufacturing. By contrast, Boston Consulting Group puts the number of unfilled manufacturing jobs at 100,000, based on government statistics. But no matter how bad the shortage is now, it will get worse, says Harold Sirkin, a senior partner at the consultancy. He predicts that number will rise to 875,000 by the end of the decade as older, more skilled workers retire.

It will also deepen as specialized, high-tech manufacturing increases in the U.S., Sirkin says. A growing number of factories use computers and robots to produce components like airplane and automotive parts, and need workers who can run computers and complex machines.

A number of factors led to the shortage. At one time, manufacturing was the heart of the U.S. economy. But as millions of manufacturing jobs were lost — between 7.1 million between 1980 and 2009 according to the Brookings Institution — manufacturing became a less steady, reliable way to earn a living. It also doesn't appeal to people who might think of gritty factories filled with heavy equipment, not the new generation of cleaner and quieter workplaces.

"We've told our kids that working in manufacturing is not a good thing. In the past, it was mostly brawn and not much brain. Now its brains, not brawn," says Sirkin, who co-wrote a Boston Consulting Group report last September about the shortage.

But business owners in all industries contribute to the problem, says Peter Cappelli, a professor of human resources management at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School. He says many owners have an unrealistic expectation that they'll continually find skilled workers although ever-changing technology means new skills are needed.

"If you're an employer, you have to be crazy to treat this like a supply chain and hope your suppliers show up at your door with what you're looking for," he says.

Pay is another issue, Cappelli says. Many owners either can't or don't want to pay what job candidates want — some are offering the sort of wages that people make in retail or fast-food restaurants.

"They're looking to hire machinists for $12, $13, $14 an hour and they want them to have computer skills," Cappelli says.

_____

DO-IT-YOURSELF TRAINING

Keats Manufacturing has five openings and three or four workers likely to retire in the near future, Chief Operating Officer Matt Eggemeyer says. The Wheeling, Ill.-based company, which has 110 employees, is already training the next generation of workers.

Keats manufactures metal parts used in vehicles, appliances and medical and electronic equipment. Because it does custom work, it needs employees who can continually adjust machinery to create different parts. It's labor-intensive work that takes years to learn to do well.

"Just being able to run the machine takes six months of training," Eggemeyer says. "Depending on the individual, it could be five years before they're really worth their salt."

Keats has tried advertising for help. Many candidates claimed they had the skills the company needed, but when they started working, it was clear they weren't qualified.

Eggemeyer compares Keats' training program with the minor league system in baseball. Employees are trained and rise through the ranks until they're considered highly skilled. It can take as long as 10 years for some to become expert tool and die makers — people who create the machinery used to make metal products.

Learning on the job isn't new, says David Zonderman, a professor of labor history at North Carolina State University. It was once common for companies to take on apprentices who were paid while they learned, and businesses often partnered with labor unions to create apprenticeship programs, Zonderman says.

The marriage of computers and manufacturing has forced many companies to do more of their own training, Zonderman says.

"Whenever there's a fairly rapid technology shift, both businesses and workers have to adjust," he says.

In-house training fell by the wayside over the past three decades as many companies tried to save on labor costs by outsourcing work and using temporary and part-time employees, says Alex Lichtenstein, a labor history professor at Indiana University.

"In an effort to increase productivity while tamping down wages, companies have thrown out the baby with the bathwater," he says.

_____

THE TEAMWORK APPROACH

Technology has also created a skills deficit for companies that do marketing and public relations. The social media explosion has created a new way of getting publicity — a blurb on Facebook or 140-character posting on Twitter that bears little resemblance to the two-page press release that is the standard in public relations. PR firms need people who are adept at all the methods, but few fit that description, says David Chapman, owner of Nine One Nine Marketing in Holly Springs, N.C.

"It's difficult to bring these two worlds together," Chapman says.

The problem is generational. Older staffers spent years writing press releases and don't think in terms of constantly posting short, quick tweets. Many younger staffers, meanwhile, haven't learned how to craft a longer story.

Chapman's solution is to team staffers so a client's message will reach all types of media. But that does mean more staffers working on an account than in the past.

"It's hurting productivity, and I can't necessarily bill my clients for that inefficiency," Chapman says.

He expects the problem to resolve itself over time. As older members of his staff of 22 leave, he's likely to hire more workers with multiple skills. Many people take PR jobs after working in TV or at newspapers, and younger journalists tend to be comfortable with all types of media, he says.

_____

THE RECRUITING STRATEGY

The super-high-skilled worker that Burt-Watts needs is going to be hard to find — and the company knows it, says Heather Merz, its chief financial officer.

The Austin, Texas contracting company has done mostly interior work, but decided in 2011 it would expand its division that constructs buildings from the ground up. It began looking for workers with highly specialized skills: They had to be knowledgeable about the Austin construction industry, specialize in "ground-up" construction and have connections with good subcontractors.

Burt-Watts decided that the usual methods of searching for candidates — advertising and word of mouth — might not work because of the job requirements.

"We started realizing, this may be a little more challenging than we thought," Merz says.

So the company decided to search more aggressively for candidates. It sends a team of recruiters to Texas colleges that grant degrees in construction, like Texas A&M. They go to job fairs to interview students in much the same way that law firms and Fortune 500 companies do. The strategy also gives the company access to experienced job candidates through alumni offices.

The company expects that it will take some time to fill its current opening for an estimator, someone who works with customers and subcontractors on a project to come up with a price. The search began in mid-January.

"We don't usually get too frustrated because we know that if we take our time we will find the right fit," Merz says.