Japan is as technology rich as it is hydrocarbon poor. The country’s proven oil reserves stand at a measly 44 million barrels. (The U.S. holds nearly a thousand times more, or 36 billion.) The Niigata Prefecture, located some 200 miles northwest of Tokyo, is one of the few places in the country that had produced domestic oil, and the streets of local towns still feature many metal works and factories that once supported the industry.

Japan is as technology rich as it is hydrocarbon poor. The country’s proven oil reserves stand at a measly 44 million barrels. (The U.S. holds nearly a thousand times more, or 36 billion.) The Niigata Prefecture, located some 200 miles northwest of Tokyo, is one of the few places in the country that had produced domestic oil, and the streets of local towns still feature many metal works and factories that once supported the industry.

One of them is the Kariwa Plant, located in a village of the same name on the blustery coast of the Sea of Japan. Though far from the country’s high-tech corridors, it has recently consummated a marriage between advanced manufacturing and the oil industry.

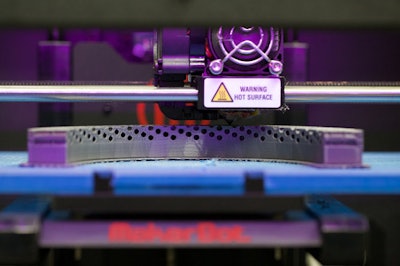

For the last 45 years, Kariwa has been making a huge variety of valves for transporting natural gas, oil and other fluids, mostly for export. GE acquired the plant in 2011, and two years later it started testing 3D printers to manufacture special control valves, whose walls are peppered with hundreds of narrow holes. While 3D printing is quickly becoming old news, this story has a twist.

The project is unusual since it combines human craftsmanship with 3D printing. The valves include arrays of tiny holes and flow channels, which had been difficult to make and had to be assembled from many parts. The plant is relying on seasoned metal craftsmen to come up with designs for 3D printing that eliminate not only the assembly, but also the need for burdensome and time consuming post-processing, like removing burrs from the holes.

“Existing methods require processes such as brazing or assembling multiple components to produce complex shapes,” says Eiji Mitsuhashi, the industrial designer who started experimenting with the technology in 2013 and is leading the project. “The metal 3D printer allows us to make a single component, simplifying the process and dramatically increasing what we can do.”

“Existing methods require processes such as brazing or assembling multiple components to produce complex shapes,” says Eiji Mitsuhashi, the industrial designer who started experimenting with the technology in 2013 and is leading the project. “The metal 3D printer allows us to make a single component, simplifying the process and dramatically increasing what we can do.”

Mitsuhashi’s team approached the project by 3D printing the part from plastic. By the end of the first year, they were making prototypes of the whole control valves, and switched to metal.

That wasn’t so simple. The design team saw that the electron beam 3D printer didn’t fix all of their manufacturing problems. “3D printing does not make everything possible,” Mitsuhashi says. “There are things that can only be done by the human hand.”

For example, existing 3D printers can only produce objects at accuracies of up to about 0.1 millimeters. But Kariwa’s seasoned machinists can work with a precision up to 100 times greater. Mitsuhashi is using them to develop optimal designs that minimize the need for finishing after printing and speed up prodction. “Through the years of experience, I can tell an error of about one one-thousandth of a millimeter by how it feels in my hand,” said one Kariwa technician.

Mitsuhashi says that the workers’ skill will allow him to take 3D printing to next level. “They show designers where our blind spots are, or provide us with hints for making the products even better,” Mitsuhashi says. The 3D printer has already helped cut the time it takes to make certain parts from two months to about two weeks.

Mitsuhashi says that the workers’ skill will allow him to take 3D printing to next level. “They show designers where our blind spots are, or provide us with hints for making the products even better,” Mitsuhashi says. The 3D printer has already helped cut the time it takes to make certain parts from two months to about two weeks.

Kariwa may not be a household name, but the new manufacturing method puts the local plant at the forefront of industrial additive manufacturing, along with 3D-printed fuel nozzles, which are already being produced for the next-generation LEAP jet engine, and other components.

Mitsuhashi’s team expects to deliver the first products in March 2015.