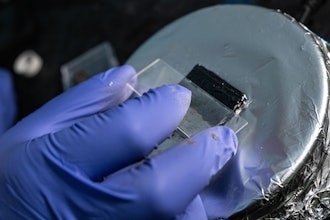

LSU Mechanical Engineering graduate student Tatiana Mello of Piracicaba, Brazil, is currently working on genetically engineering and optimizing E. coli bacteria to produce bioproducts, like biodiesel, in a cost-effective manner. This undertaking has garnered the attention of many in the engineering and biology fields and has also given her the opportunity to speak about her research at the recent National Biodiesel Conference and Expo in San Diego.

Mello proposes using E. coli bacteria to expand biodiesel production by creating a new type of feedstock.

"The main feedstocks used in the U.S. for biodiesel are soybean and corn oil," she said. "The actual production is enough to feed us, but you have the surplus that nobody knew what to do with, so biodiesel was created. This market is growing and growing. They expect within a few decades, the surplus won't be enough to produce biodiesel. E. coli is cheap and abundant, and you can just genetically modify it to fulfill this need."

Mello's main goal is to create Malonyl-CoA bioproducts, such as biodiesel, plastics, polymers, and pharmaceuticals. Malonyl-CoA is found in bacteria from humans and has important roles in regulating fatty acid metabolism and food intake; it's also an attractive target for drug discovery.

"Malonyl-CoA maximization is the topic of my research because it's a precursor for so many things," she said.

Mello, who has worked on this project for two years, had the privilege of presenting her project at the National Biodiesel Conference and Expo in San Diego last month. Only 12 university-level science majors in the country who are interested in learning about the biodiesel industry receive travel scholarships to attend. However, only four of those students are asked to present their research.

Mello did so as part of the Next Generation Scientists for Biodiesel, of which she is a member. She said attending the conference not only impacted her career and research, but also her understanding of the biodiesel industry.

"I was opened up to a new world after the misconception about the food industry and the biofuel industry competing for cropland was demystified," she said. "The many new concepts, regulations, and issues presented during the fast-paced event prepared me much better for the entire biodiesel business."

After earning her bachelor's degree in biological sciences at the University of Campinas (Unicamp) in São Paulo, Mello decided she needed one more degree in order to apply her scientific knowledge.

"First I got into biology because I was all about studying life," she said. "It fascinated me. When I was finishing my biology degree, I realized I couldn't apply anything to what I was studying. Those were the engineers. I needed bioreactors and machinery. So, I decided to get an engineering degree."

Mello stayed at Unicamp, where she earned her ME degree and then began working for Caterpillar Inc. in Brazil.

"While there, I realized I wanted to combine my two bachelor degrees," Mello said.

She connected with LSU ME Professor Marcio de Queiroz, who is also from Brazil and now serves as her advisor. She also has co-advisors, such as LSU Biological Sciences Professor Grover Waldrop, and says they all work together and have submitted a patent on her project.

Mello is set to graduate from LSU in May and plans to stay in southeast Louisiana, hopefully finding a job in the Baton Rouge area. Of course, it all depends on which company will be open to her new idea.

"We have this method, and it's working, but we need industry partners to scale it up," she said.

(Source: Louisiana State University)