Chemical manufacturing is no new endeavor. But a team of Caltech scientists say there are still breakthroughs to be had — and they’ve recently had one of them.

The team has discovered a method for producing a group of silicon-containing organic chemicals — often used in pharmaceuticals and other advanced materials — without relying on expensive precious metals. Instead, they’ve figured out how to use a chemical they say is commonly found in labs around the world: potassium tert-butoxide.

The finding is particularly significant because of the benefits of switching to the potassium salt — it not only produces a more effective catalytic process, the material is cheap and in abundant supply, unlike the precious metals in most catalysts that are rare and will eventually be scarce.

One of the scientists on the team, Anton Toutov, is a graduate student who recently won the Dow Sustainability Innovation Student Challenge Award for this work.

"We're very excited because this new method is not only 'greener' and more efficient, but it is also thousands of times less expensive than what's currently out there for making useful chemical building blocks. This is a technology that the chemical industry could readily adopt," Toutov said.

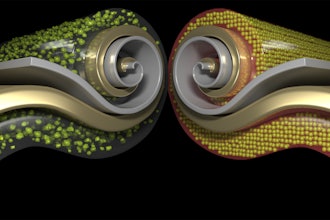

The finding has garnered intense interest in the chemistry world because it provides a simple solution for driving a challenging catalytic process that replaces a carbon-hydrogen bond with a carbon-silicon bond to produce organosilanes. These new molecules are the building blocks of many chemical products including pharmaceuticals. They say this discovery could also hold promise for developing new products including materials used in LCD screens, organic solar cells and new pesticides.

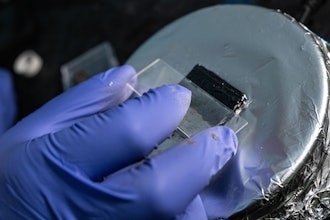

According to Toutov, the new catalyst also seems to be robust enough to scale up to a large, manufacturing level. To prove it, they used the catalytic process to synthesize nearly 150 grams of valuable organosilane, which they say is the highest amount ever produced by a single catalytic reaction. They reported that the reaction required no solvent, only generated hydrogen gas a byproduct and ran successfully at -45C as the lowest reported temperature.

The findings were reported in the most recent issue of Nature — and the authors say it’s been generating buzz when presented to industry chemists.

"People constantly try to tell us how mature our field is, but there is so much fundamental chemistry that we still don't understand," said Brian Stolz, one of the study’s coauthors and a professor of chemistry at Caltech.

Learn more about the study here.