BILLINGS, Mont. (AP) — A long-delayed cleanup proposal for a Montana community where thousands have been sickened by asbestos exposure would leave the dangerous material inside some houses rather than remove it, as government officials seek to wind down an effort that has lasted more than 15 years and cost $540 million.

Details on the final cleanup plan for Libby, Montana, and the neighboring town of Troy were to be released Tuesday by the Environmental Protection Agency.

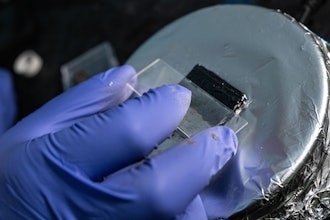

Asbestos would be left behind knowingly only where it does not pose a risk of exposure to people, such as underground or sealed behind the walls of a house, EPA project manager Rebecca Thomas said.

Yet some residents worry the material eventually could escape and re-contaminate their community.

The EPA has spent $540 million since 1999 trying to address the deadly asbestos dust from a W.R. Grace & Co. vermiculite mine that operated outside Libby for decades. That work will continue for three to five years, with several hundred commercial and residential properties still to be addressed, Thomas said.

Asbestos-containing vermiculite from the Grace mine was used as insulation in millions of houses across the U.S. In Libby, contaminated waste from the mine was unwittingly used by many residents as a garden-soil additive and as fill for the local construction industry.

"You might have vermiculite in the walls. But as long as it's sealed within plaster or behind drywall and nobody can breathe it, it does not pose a risk," Thomas said.

An EPA research panel concluded last year that even the slightest exposure to asbestos from Libby can scar lungs and cause other health problems. Health workers estimate as many as 400 people have been killed and almost 3,000 sickened in Libby and the surrounding area by asbestos exposure.

Mike Noble, a retired Grace worker who now chairs an EPA advisory group in Libby, said it's inevitable that some of the material now trapped inside residential walls will get out.

"We've left a lot of this behind in these houses, and you always have the potential of people opening up that wall and running into it," Noble said. "Either we have a small fire in the house or want to do a renovation or someone's playing too rough and they kick the sheet rock in."

To guard against such accidental releases, Tuesday's plan will outline a series of institutional controls designed to educate residents and contractors about what to do if they encounter asbestos, according to state and federal officials.

The Libby area would remain for now in the EPA's Superfund program.

Eventually, the community likely will lose that status — and much of the federal funding that goes with it. At that point, oversight for the institutional controls will become the responsibility of the Montana Department of Environmental Quality.

"We know they are going to work only if we can get the community to buy in," said Jeni Garcin-Flatow with the Montana Department of Environmental Quality.