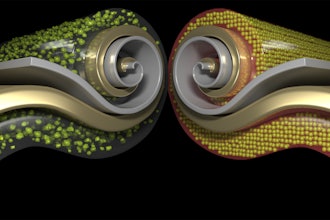

An international research team co-led by a Monash biologist has shown that methane-oxidising bacteria -- key organisms responsible for greenhouse gas mitigation -- are more flexible and resilient than previously thought.

Soil bacteria that oxidise methane (methanotrophs) are globally important in capturing methane before it enters the atmosphere, and we now know that they can consume hydrogen gas to enhance their growth and survival.

This new research, published in the International Society for Microbial Ecology Journal, has major implications for greenhouse gas mitigation.

Industrial companies are using methanotrophs to convert methane gas emissions into useful products, for example liquid fuels and protein feeds.

"The findings of this research explain why methanotrophs are abundant in soil ecosystems," said Dr Chris Greening from the Centre for Geometric Biology at Monash University.

"Methane is a challenging energy source to assimilate.

"By being able to use hydrogen as well, methanotrophs can grow better in a range of conditions."

Methanotrophs can survive in environments when methane or oxygen are no longer available.

"It was their very existence in such environments that led us to investigate the possibilities that these organisms might also use other energy-yielding strategies," Dr Greening said.

Dr Greening's lab focuses on the metabolic strategies that microorganisms use to persist in unfavourable environments and he studies this in relation to the core areas of global change, disease and biodiversity.

In this latest study, Dr Greening and collaborators isolated and characterised a methanotroph from a New Zealand volcanic field. The strain could grow on methane or hydrogen separately, but performed best when both gases were available.

"This study is significant because it shows that key consumers of methane emissions are also able to grow on inorganic compounds such as hydrogen," Dr Greening said.

"This new knowledge helps us to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases. "

Industrial processes such as petroleum production and waste treatment release large amounts of the methane, carbon dioxide and hydrogen into the atmosphere.

"By using these gas-guzzling bacteria, it's possible to convert these gases into useful liquid fuels and feeds instead," Dr Greening said.