As environmentalists, industry groups and policymakers continue their decades-long fights over appropriate regulation of pesticides, scientists are working on alternative methods to control what is likely the most lethal pest in human history: the mosquito.

The New York Times and PBS' "American Experience" this week chronicled the roots of the pesticide debate — and where to turn next — as part of the paper's "Retro Report" documentary series.

The video detailed the proliferation of the potent insecticide DDT in the mid-20th century, when it was used to prevent agricultural pests and sprayed in neighborhoods to the point where it nearly eradicated malaria — the most notorious of many mosquito-borne illnesses to plague humans.

In 1962, however, Rachel Carson's landmark book "Silent Spring" detailed the adverse environmental impacts of DDT and helped spawn the modern environmental movement. The U.S. and other developed nations largely banned the use of DDT in subsequent years.

Conservative critics alleged that insecticide bans were to blame for the re-emergence of malaria in the developing world, but the documentary noted that evolution was actually the culprit.

DDT was never banned in many parts of Africa or Asia; instead, mosquitos in those areas developed resistance to the chemical and malaria rates — and fatalities — soared.

The number of illnesses fell in recent years amid advances in medical technology and insecticide-laden bed netting, but scientists warned that those methods are also ultimately fighting a losing battle with mosquito evolution.

Instead, some are looking to more innovative solutions.

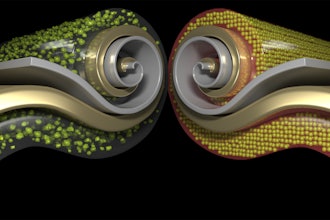

University of Maryland entomologist Raymond John St. Leger is developing a fungus laced with spider venom that could kill mosquitos that absorb it.

George Dimopoulos, an immunologist at nearby Johns Hopkins University, also hopes to genetically modify mosquitos and utilize helpful bacteria to prevent them from ever contracting the malaria parasite.

Such "holistic" systems could help curb the need for chemical insecticides, but scientists cautioned that many different approaches would be needed to combat the mosquito.

“The solution isn’t going to be relying on any single technology as the silver bullet.” St. Leger said.

Scientists Seek New Methods as Insecticides Fail to Combat Mosquitos

As environmentalists, industry groups and policymakers continue their decades-long fights over the appropriate regulation of pesticides, scientists are working on alternative methods to control what is likely the most lethal pest in human history: the mosquito.

Jan 25, 2017

Latest in Chemical Processing

Jury Awards $332 Million to Man in Monsanto Case

November 3, 2023

EPA Boosts Biofuel Requirements

June 22, 2023

Bayer Owes $6.9M Over Weed Killer Advertising

June 16, 2023