Humans have been waging a tit-for-tat war against mosquitos for decades. In a way, these tiny insects are one of our biggest enemies.

It’s estimated that mosquito-related illnesses, including malaria and dengue fever, kill about a million people each year. Now, with the recent spread of Zika raising concerns about a possible link to microcephaly — the devastating illness that causes babies to born with shrunken brains and heads — many are asking yet again: Can’t we just get rid of mosquitos for good?

There’s no simple solution to this problem. But here’s a look at the various arguments surrounding the issue:

Kill Them With Pesticides!

Our most notable successes with eradicating mosquitos has been with the help of chemicals. The hero-turned-villain of this story is, in fact, the now dreaded DDT. After its discovery in the late 1900s, the use of DDT was responsible for the U.S. being able to declare itself “malaria free” in 1949.

But, of course, DDT exposure has since been linked to several long-term health issues, including breast cancer, and is known persist in the environment for decades, which is why most countries have banned its use. DDT is, however, still being sprayed in parts of Africa where malaria kills tens of thousands of people every year — though scientists caution that DDT spraying should be closely monitored and restricted.

The other pesky thing about these pests is that they tend to develop a resistance to chemicals, which is why many scientists are on the hunt for new chemical alternatives that could shrink mosquito populations.

Last year, a team of researchers from Purdue University released a study identifying a new class of chemical insecticides they say could provide a safer means of targeting the types of mosquitos that transmit disease. The researchers used “the mosquito genome to pinpoint chemicals that would be more selective than current pesticides.” While the research is promising, significant challenges remain to commercializing the technology and making sure it doesn’t harm other wildlife.

In short, pesticides can only go so far in wiping mosquitos off the earth.

Kill Them With Genetic Modification!

Scientists using genetic modification have recently offered a host of promising ways to stop the spread of mosquito-related illnesses.

Some are looking at a modification that edits out the part of the mosquito genome that carries infectious diseases. Another team of scientists at a British company called Oxitec created a “self-limiting gene” that, when introduced into the wild in male mosquitos, gets passed to offspring who are then unable to mature into adults.

Though successful in labs, many have noted that using this kind of method could be impossible on a larger scale — and that it could cause unforeseen consequences.

Kill Them With Bacteria!

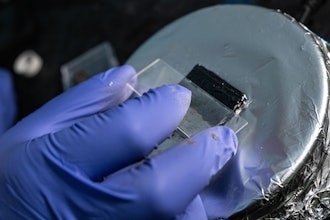

Another method scientists are studying involves injecting mosquitos with a bacteria called wolbachia, which prevents viruses from growing inside mosquitos. This way, a virus like Zika would die before a mosquito that has bitten someone who’s infected is able to bite someone else and pass the disease on.

Scientists are worried that this fix would be short lived, however, because viruses can mutate quickly to become resistant to bacteria. So researchers are now considering the possibility of infecting mosquitos with more than one strain of the bacteria at a time. We infect them, which means they don’t get to infect us.

Don’t Kill Them at All!

Even if we could kill mosquitos — should we? The question is partly philosophical and partly practical.

As far as the food web is concerned, there are worries that even if someone could wave a magic wand and poof all mosquitos out of existence, it could have a disastrous effect on the wildlife, including frogs, bats and birds, who rely on mosquitos for their diet. Yet, other scientists argue that those animals will just find other bugs to chow on. Bottom line: This disagreement means scientists don’t know what the ripple effect through the environment would be.

That issue, coupled with many people’s distaste for “playing God,” is why some say we should be focusing our efforts elsewhere, such as encouraging more pharmaceutical R&D investment into finding vaccines and treatments for these diseases. Although there’s less financial incentive for pharma companies to research diseases that affect people in poorer countries, political pressure could help scientists spring into action. Earlier this month Obama called on U.S. health officials to help speed the development of tests, vaccines and treatments to combat Zika.

No matter which way you side, there’s no clear-cut solution to stopping these diseases. If we manage to win another big battle against the mosquitos, it will likely be from using a combination of these approaches rather than any one method alone.