Tucked in the bone-dry plains of southeastern Colorado, a vast field of nondescript military buildings and steel igloos house an ongoing project that is both historically significant and dangerously complex.

The igloos were built in the 1950s to store about 780,000 unused WWII-era chemical weapons including the deadly sulfur mustard agent. Last year, work began to destroy the munitions at the $4.5 billion Pueblo Chemical Agent-Destruction Pilot Plant, which was finished in the summer of last year.

It’s a high-risk operation. Even minimal exposure to sulfur mustard can damage eyes and cause skin rashes and large puss-filled blisters. At a high enough level, exposure can be fatal.

The employees at the plant have a range of technical know-how — from chemical engineering to military training and experience working at power plants. But for some of the most perilous parts of the operation, the military is getting a little help from a first-of-its kind robotic operation.

Bombs Away!

A workforce of about 1,400 remotely operate robots and forklifts to carefully disassemble the bombs. The process is a bit like reverse manufacturing, and the staff must have intricate knowledge of how the munitions were constructed to know the safest way to pull them apart.

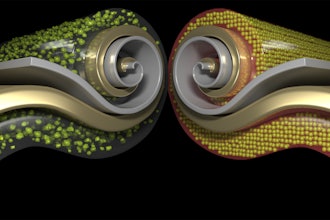

According to a recent report in Ars Technica, the bombs were built by filling part of the casing of each artillery with chemical agents and then hydraulically pressing a burster well into the shell. Explosives were then inserted into the burster well and the wine-bottle shaped shells were capped off with a fuse well cup. The shells were cold cast so that they would fracture when exploded and effectively disperse the chemical agent.

To destroy the bombs, 12-foot tall robots operated remotely work on multiple production lines to remove the lug, projectile and burster rod of each bomb. Once the explosives have been removed, the casings — still containing chemicals — are moved with an autonomous forklift to another part of the plant.

For that part of the process, robots bust open the neck of the munition and drain the chemical agent into titanium containers. Robots also inject a mix of 190-degree water and sodium hydroxide in the chemical to decrease its acidity and reduce it to hydrolysate. The liquid is then run through a series of pumps and steam equipment to break it into a fine molecular mist.

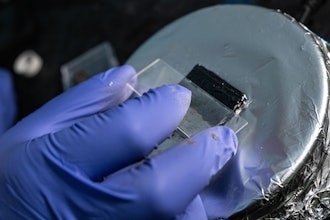

Finally, the mixture is sent into a reaction tank where it is broken down further by special bacteria from sludge that eats compounds like hydrolysate.

By the very end of the process, all that remains is empty munition shells and salt cakes that are sent to a hazardous waste landfill.

When the plant is fully operational, it is designed to destroy an average of 500 shells a day. It is expected to take about four years to destroy the entire stockpile. Once all of the work is complete, the company that built the plant plans to close down the entire operation.

Check out this video about the five steps used by robots at the Pueblo Chemical Agent-Destruction Pilot Plant.