BELLEVUE, Wash. (Hartman Group) — Childhood obesity is a term that has infiltrated American society in almost every health-related message out there. There's been quite a bit of commotion in the past year surrounding regulation and mandates and packaging and marketing to kids, and while the focus on products and nutrition panels has been somewhat helpful, let's talk about a potential — and largely unaddressed — game changer in the realm of obesity in America: the culture of how America eats... and eats too much.

If the pragmatic problem is that we eat too much, the more tragic problem is that, as a society, we appear remarkably ill-equipped to confront the problem directly. Instead, we’re treated to a teach-and-tinker approach with vague platitudes like: "learn to eat healthy," "get plenty of exercise," and "watch out for junk food." In truth, those solutions will never prove effective if we continue to indulge at our current caloric pace.

Since 2004, when childhood obesity was deemed a public health crisis, not only has there been an increase in focus and discussion around products, nutrition panels and mandates (i.e., what we eat), but there has also been a steady increase in children's health education programs, notably with Michelle Obama's Let's Move initiative implemented in 2010. In fact, 80 percent of people support efforts to include more intensive education about obesity and healthy eating in schools; children between the ages of 8-12 are becoming more aware of weight issues and healthy eating as schools incorporate health and nutrition programs and look to improve school lunch programs.

Sure, educating our children about how to pursue health and wellness is one part of the fight against childhood obesity and has the potential to feed back into the family dynamic, but our research doesn't show any noticeable correlation between nutritional awareness and education and one’s waistline. The Hartman Group has instead found a group of very well-read, informed consumers who continue to battle the bulge. The time has come to stop focusing on just the parts, which to date have included education on packaging and nutritional panels, placing the blame on manufacturers and QSRs, and noting the availability of "bad" food; instead, we must start to focus on the whole, which is essentially a cumulation of how we, as Americans, eat and its direct effect on how much we're eating.

Parents & Children: A Shift in Influential Power

We’ve all heard that it begins with the parents. In fact, 85% of consumers believe that parents are responsible for what their children eat; consumers nearly unanimously attribute obesity to the individual except in the case of children where parents are assigned the blame. Still, many consumers believe that hectic American lifestyles lead to poor eating habits in order to meet family priorities around time management rather than weight management.

Since the 1950s, there has been an uptick in the influence kids have in what is bought at the grocery store. This identifies a shift from parents holding the authority in buying decisions to a more democratic environment. Older kids have always taken part in more unsupervised eating than the younger kids, and today, that style of eating is only magnified as fewer families eat together and more people in general are eating—not only meals, but also snacking—alone.

Simply put, when we eat alone, we eat unconsciously, and eat more; there is no one there to see what we’re choosing to eat and how much of it we’re eating. We appear to be eating much more food, far more frequently, and mostly alone, than at any previous point in American history.

And hence, we arrive at the core point: We must understand that eating is first and foremost a cultural and social activity. Most peoples throughout civilization have traditionally eaten in this fashion, making eating one of the fundamental rituals of social life.

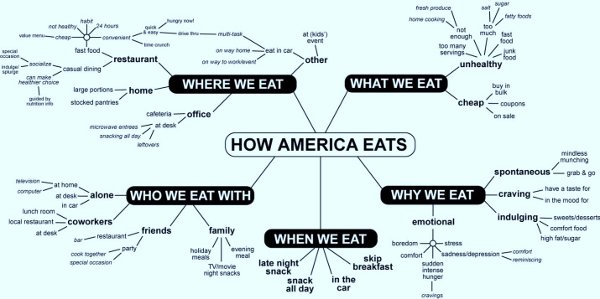

Consumers perceive “How America Eats” as the cause of obesity

|

Commensality: Social Eating as a Tool for Change

The physical act of eating together, or commensality, actually serves to regulate food portioning and food consumption. Besides the calorie control factor, commensality also promotes other healthy practices, like:

- Reinforcing social bonds, values and norms (i.e., what is edible vs. inedible)

- Lending stimulus to regular, routine gathering of the group

- Providing reliable time for communication within the group

Ritualistically disbursing shared food (as opposed to self-service) also offers a natural method of portion control; makes compulsive eating virtually impossible due to the audience; makes the individual accountable to the group for what is eaten; and, ideally, reinforces the social structure of the group through division of labor involved in cooking and serving food.

So how can marketers use this information? Encourage planning and socialization of snacking and indulgence eating. Tell us to enjoy ourselves, but to enjoy ourselves socially, not in isolation. It may not really prevent someone from gaining weight all by itself, but it demonstrates empathy for the dark side of our most favorite eating. It also sanctifies our hedonistic urges and avoids the possibility that your product or brand will become seen as a killjoy by a yo-yo dieter in a foul mood.

Companies can devise marketing campaigns that demonstrate empathy for our cultural love of snacking while stimulating us to think of creative ways to socialize it. These should not focus on demonizing “bad foods” but rather on transforming snacking into a memorable, social experience like it used to be (i.e., afternoon tea, after-school treats, etc.).

Amy Sung contributed to this Hartbeat article. Amy’s passion is writing about food culture. She has written for various industry publications and websites.