This is the second part of a two-part series on engineer Mel Terry and his invention, the Wheelift transporter. Read the first part here.

The Wheelift In Action

The aerospace industry was one of Terry’s first targets when it came to finding customers for the Wheelift transporter. Manufacturers of airliners and fighter jets alike regularly need to lift loads between 35 and 75 tons, and with an incredible degree of precision. The capability to be partially or fully automated is also a major plus when it comes to the small tolerances in assembly that can make the difference between a plane that flies and once that doesn’t.

Unfortunately, most current AGVs aren’t capable of carrying such heavy loads — they’re often limited to 10 tons, which puts them below the thresholds for the massive parts, such as wing sections or engines that need to be transported to the plane for assembly. The list of locations where Terry’s creation has made an enormous impact is already long and impressive, but it’s still growing.

F-35

The Wheelift’s ability to overcome these restrictions is one of the reasons it was chosen to be part of the current F-35 Lightning II Program, also known as the Joint Strike Fighter, as part of an automated guided vehicle (AGV) system designed by KUKA Robotics. By utilizing Wheelift transporters, the systems were able to be designed so that aircraft could be built in machine cells — a typical configuration in a manufacturing plant producing much smaller items.

Doerfer provided a five-vehicle “free range” system, which included three 38,000-pound AGVs with two additional 75,000-pound AGVs and a central Control & Indication server (C&I) that serves as the heart of the automated system. The C&I communicates with an AGV server, which manages all tooling/work-in-progress moves. Both servers allow the system to be completely flexible based on the current needs, in addition to priority routing, safety and fault tracking.

Terry says that the low-profile Wheelift chassis with an integrated lift eliminates the need for other material handling mechanisms, such as cranes, to provide tooling access to the part. The F-35 program also appreciates the incredible accuracy of the transporters. Terry says, “The Wheelift uses an AC control system. That means we’re using servomotor drives — that’s like the precision drive used in a milling machine. We can dial in to move a few thousandths of an inch, and it will move a few thousandths of an inch.”

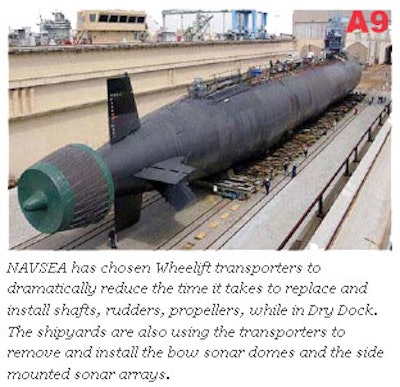

In The Navy

NAVSEA has chosen Wheelift transporters to dramatically reduce the time it takes to replace and install shafts, rudders, propellers, while in Dry Dock. The shipyards are also using the transporters to remove and install the bow sonar domes and the side mounted sonar arrays.The Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) has also selected the Wheelift transporters for dry docks and machine shops in order to conduct necessary maintenance on massive crafts that monitor the seas worldwide. The plan was to provide eight 150-ton transporters, each of which is capable of being operated independently or as a group of any size. As a single unit, the transporters can carry 200 tons, and two or more units can work in tandem for larger loads. All are controlled via wireless controllers. These massive capacities come in handy when NAVSEA needs to lift a new propeller or rudder into one of its ships.

NAVSEA also required that the transporters they specified be capable of delivering positioning better than 0.005” — an incredibly difficult proposal considering that one of the propellers can weigh nearly 80 tons, and that the facility is often bombarded by strong winds and sea spray. Terry was confident that the Wheelift would be able to meet these specifications. He says, “They’re able to join components together within thousandths of an inch. It’s incredible. They’re doing it every day.”

Neutrinos?

Doerfer’s Wheelift transporters were chosen to handle the underground movement of large components at theDayaBaynuclear plant inChina, where the US Department of Energy (DOE) and the Chinese Institute of High Energy Physics (IHEP) are jointly trying to study neutrinos, which are invisible, mysterious particles emitted by the sun and nuclear fission here on earth.

A major contributor to the savings of millions of dollars on this project is the low profile and precision omni directional travel capability of the Wheelift transporter. The company provided an eight-axle transporter rated for 130 metric tons, which they called the “Ox” in honor of the Chinese calendar. While the Wheelift transporter is not tied to the actual process of discovering neutrinos, Terry is proud to explain how it helps move eight massive underground detectors around two miles of tunnels running through solid granite mountains. By using the nimble Wheelift transporters, the tunnels were able to be one third smaller than necessary for any other type of underground system.

Those detectors, known as “liquid onions,” are made in three layers. Central-most is 20 tons of organic liquid scintillator containing gadolinium—a heavy rare-earth metal—followed by another layer of liquid scintillator without gadolinium. The outermost layer uses mineral oil, and it adds together to 100 metric tons of precise machinery that must be kept level and at absolutely minimal g-forces during movement. Operators are then able to control the movement of the Wheelift transporters and their payloads via a wireless joystick controller, while the on-board guidance system steers clear of the granite walls. And this process of moving around the “liquid onions” is almost continuous, as scientists need to verify their data. Sound precise enough?

Where next?

Perhaps the greatest testament to any innovation’s real value is how it lasts in a rapidly-changing marketplace. Terry is confident that his system will continue to be relevant to manufacturers of heavy equipment for decades to come, as automation becomes more integral into operations and we always strive to make things better and more quickly.

Terry says that he wants to get Wheelift transporters into mining facilities, where companies need to move vast amounts of heavy material or large machines in notoriously difficult underground environments. Same goes for the nuclear industry, which deals in large quantities of raw materials and wastes. In the automotive industry, his transporters could find a good deal of use moving around dies, or transporting molds in plastics manufacturing plants. He says, “It just totally changes how companies can build their products. And that’s what the story is all about.”

More than anything, Terry’s story is a perfect example of how years of hard work toward an idea — along with a little perseverance — can lead to fantastic places. That, in essence, is the mission of product development and of engineering: the creation of a lasting technology that has the potential to change the way others do business. Clearly, the Wheelift is well on its way to disrupting the status quo of heavy-duty manufacturing.