Word on the street is that substantial portions of previously offshored manufacturing operations are due to return to the United States.

A number of macroeconomic factors seem to have tipped the balance in favor of domestic manufacturing. Among them, for example, are the appreciation of China’s currency versus western currencies, labor rate inflation, increased concerns about supply interruption and adulterated product and lowering energy cost in the United States due to prospects of shale gas. Even President Obama’s administration, banking on these trends, is actively encouraging companies through its “Make It In America” campaign to shift manufacturing back to the United States to create jobs and increase the country’s competitiveness on the international stage.

The return of a few companies’ manufacturing is encouraging. But the big question is: To what extent is the United States capable of taking back manufacturing on a significant scale? The challenges are great.

From a broad supply chain ecosystem perspective, for example, companies obviously will need to rebuild a supplier network that may have evaporated, along with the disappearance of the manufacturing operations it supported. They also will need to consider rerouting functional interfaces, such as with their product development department that, in some cases, also migrated offshore.

But more fundamentally, two key areas that ensure the United States’ manufacturing competitiveness were severely neglected over the past decade. They must now be addressed:

- Equipment maintenance and upkeep have been ignored or postponed. In fact, U.S. manufacturers have typically invested less than 5 percent of revenue in capital equipment, compared to the 6 to 9 percent that’s usually required to keep up with top performers, according to the 2011 Next Generation Manufacturing Study/Survey from the Manufacturing Performance Institute.

- The operational expertise residing in the minds and practices of laborers, engineers and technicians is quickly dissipating as these workers retire, and companies have no immediate replenishment of that talent in sight.

These two challenges will be particularly important for industries that require high capital investments and highly skilled workers to operate and maintain the machinery.

Aging Assets

The average age of manufacturing assets and equipment currently in operation in the United States, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, is close to 20 years, and since 1990, the age of assets has virtually doubled (see Figure 1).

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, while companies have been investing in efficient, state-of-the-art technology for their overseas manufacturing facilities, their existing U.S. plants have not benefited from similar capital flows into new or upgraded equipment. This lack of investment has two major implications.

First, manufacturing productivity decreases as assets age. Older machines tend to experience progressively more downtime, causing both more planned and more unscheduled maintenance, which in turn can lead to lower output and higher cost per unit. This isn’t necessarily a show-stopper, provided that plant maintenance and upkeep programs are in place to maintain asset productivity and to extend the life of the assets. Unfortunately, most companies have not invested sufficiently in these programs over the years and have sacrificed maintenance and upkeep as they were trying to survive in harsh economic conditions.

Second, any additional increase in manufacturing activity may require investing significant capital in new facilities or equipment as the existing assets may be unable to absorb the extra load. Even though, on aggregate, capacity utilization in manufacturing is still below 80 percent, this buffer has become much smaller in energy-intensive industries which are among the first ones that considered a return to the U.S., attracted by the potential of lower energy costs due to shale gas. Even if the assets in place are still appropriate for the task, there may not be enough capacity to take on the returning volume.

At best, the needed investments to address the issue of the aging asset base could delay the return of manufacturing to the U.S. since, even if the capital is there, it’ll still take some time before the new or upgraded equipment is up and running. At worst, some companies facing capital constraints may find the business case for bringing manufacturing back to the United States falling short of their internal capital return hurdles and may have to put their return plans on ice indefinitely.

Aging Workers

The feasibility of manufacturing in the U.S. on a significant scale may largely depend on companies aggressively driving maintenance excellence and making capital available for upkeep or upgrade programs. However, the sustained success of these returning manufacturing activities will depend on those companies accessing and keeping the expertise and skills required for operating their plants.

Like mechanical assets in U.S. plants, the domestic manufacturing workforce is also aging. According to the Economics and Statistics Administration, the average age of this workforce is about to cross 45 (see Figure 2.) and it’s estimated that 10 percent of the current manufacturing workforce will retire in the next 3 to 5 years.

A complicating factor is that in many manufacturing environments, most knowledge resides in the minds and practices of these seasoned workers who have honed their skills and built their expertise over decades. Unfortunately, their expertise, like that held by a diminishing number of older workers across the U.S. manufacturing landscape, has not been codified and is at risk of being lost upon their retirement. Examples like this stress the importance of systematically identifying processes that are heavily reliant on people expertise and codifying them into standard operating procedures and documented process recipes, before they are lost.

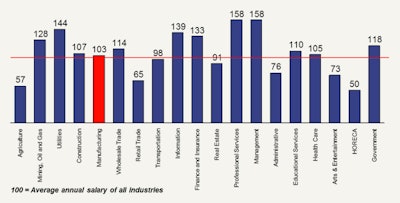

Not only will U.S. manufacturers have to stem the rapid loss of valuable knowledge that is not easily replicated or replaced, but they will also need to step up recruiting and training of new workers to manage and carry out the returning manufacturing activities. As they ramp up their recruiting efforts, they will find themselves competing with other sectors that may be more appealing to new job seekers. Many younger workers are still skeptical about the long-term viability of manufacturing jobs and there’s still a strong perception that manufacturing work is dangerous and dirty, to name a few of the negative connotations that are associated with production labor. They see other sectors as more attractive, even when these sectors pay less than manufacturing jobs (See Figure 3.), because they appear to have more comfortable working conditions and require fewer technical skills.

In 1970, 25 percent of the U.S. workforce was in manufacturing-related activities. Today, this figure has dropped to less than 9 percent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. As a result, the Manufacturing Institute’s 2011 Skills Gap Report noted that as many as 600,000 U.S. manufacturing jobs remained vacant across the country due to shortages of skilled workers and a more recent survey of more than 800 U.S.-based manufacturers indicated that 90 percent of them face a shortage of skilled production employees. It’s only logical that the competition for talent that can manage and operate manufacturing assets will only heat up as companies look to bring back their operations.

Figure 3

Conclusion

If manufacturing is looking to make a comeback and is going to have a sustainable future in the United States, then government programs that proactively drive that agenda through the provision of investment, appropriate education, and other measures will be required. But these programs alone are not sufficient.

U.S. manufacturing companies will need to work hard to overcome the constraints they face due to aging assets and workers.

Aging assets will require significant commitment of capital to build new plants or make targeted investments to extend the life, and increase the productivity, of existing assets. In parallel, companies will need to revitalize their maintenance and upkeep programs in the short-term and, longer term, they need to review their overall maintenance strategy and execution plan to achieve maintenance excellence in order to keep productivity increases in line with or ahead of the salary increases that will result from the competition for labor.

The aging workforce will force companies to think strategically about recruiting, training and retaining talent and about putting in place processes to capture both current and future knowledge. Simply investing in more effective traditional talent management approaches such as functional training, classroom instruction, mentoring and competency models, will no longer be sufficient to enable success. Instead efforts need to be elevated to create a genuine talent strategy that addresses long-term capacity planning, innovative methods to accelerate skills and develop leadership, an understanding of the value of the work itself, and the intrinsic value of creating a strong brand proposition for employees.

Those companies that have already invested in their manufacturing assets to facilitate a return to the U.S. may luck out in the short term, in the sense that they had first-round picks when they were staffing up their newly invigorated domestic operations. But they will soon see labor costs go up as other companies try to return and start targeting that same talent pool. So even as early returners, if they didn’t invest enough and decided to just touch up the old equipment, they will still quickly see lower productivity and higher salaries impact their competitiveness in the mid- to long-term.

And for those manufacturers that are still contemplating their return to the U.S. and still determining the investments and launch efforts required to address their aging assets and aging workers, they will need to revise their decision models with higher costs and lower productivity than they may have been expecting. They will need to be confident the return will be worth it in the long run and that their customers will value (and will be willing to pay extra for) that “Made in America” label.

Commitments like the one made by Bill Simon, President and CEO of Walmart U.S., this past January — that his company will buy an additional $50 billion in U.S. products over the next ten years — can go a long way toward convincing those manufacturers to take the leap. And as more companies make such a commitment, the magnitude and speed of the comeback of manufacturing in the United States may match the hype after all.

About the Authors:

Patrick Van den Bossche is the Americas Lead Partner of A.T. Kearney’s Strategic Operations Practice. He can be reached at [email protected]. Pramod Gupta is a principal with A.T. Kearney. He is based in New York and can be reached at [email protected]. Chui Lee is a principal with A.T. Kearney. She is based in New York and can be reached at [email protected]. Hector Gutierrez is a consultant with A.T. Kearney based in San Francisco.