Larry Thompson

Larry ThompsonEveryone knows that American manufacturers doing business in places like China risk having stolen their most trade precious secrets—whether it’s source code, R&D reports, or blueprints. And it’s the rare case that a company like American Superconductor of Devens, Mass., can find satisfaction in court as it did in January, when accused customer Sinovel Wind Group of Beijing was found guilty of paying an American Superconductor employee $1.7 million to steal the source code for the company's electronic components. Whether Sinovel actually pays damages is anybody’s guess. Still, it’s easy to understand why intellectual property (IP) theft is at the center of the burgeoning trade war between the U.S. and China.

As this example shows, while companies need to take precautions to protect their IP from outside threats, it’s often insiders—employees and contractors—that do the dirty work, so they can’t be ignored

We know from Verizon’s Data Breach Investigations Report (2018), that 89 percent of such attacks in the manufacturing sector are highly targeted. Of those, at least half involve the theft of IP. A hardly negligible 13 percent of all breaches comes from company insiders.

A much starker view of internal risks emerges from the Insider Threat Report 2018, a survey of several different industries. Nine out of 10 of all organizations surveyed say they feel vulnerable to insider attacks; and 53 percent of them have suffered breaches in the past 12 months. Among the key risk factors: Nearly four in 10 people claim there are too many users with access privileges to sensitive data. Whether insider attacks are caused by malicious intent or inadvertent mistake, the result of copying, e-mailing, sharing, or printing sensitive IP can be a costly disaster.

Without an audit trail to trace the intrusion—from a company insider or a trusted subcontractor, partner, or supplier—a manufacturer can’t adequately protect itself to prevent future attacks on its IP.

So, what should manufacturing businesses do? At the very least, take these four steps:

- Form a risk SWAT team.

- Draw up a risk profile for every job in the organization.

- Deploy employee monitoring and user and entity behavior analytics (UEBA).

Let’s consider these one at a time.

First, select the key stakeholders in your company who need to create policies and procedures for protecting your IP—and for springing into action in the event of an insider breach. Put those folks in charge of appropriate use training and deciding who gets access to all intellectual properties. Often, the responsibility falls to someone in IT. But this isn’t enough. At a bare minimum, consider a team that consists of the chief information officer, the chief information security office, the heads of R&D and of manufacturing, along with your legal counsel and the head of human resources.

Your CIO should develop and oversee a proactive approach to leveraging the people, processes, and technology in order to safeguard your IP from the point of view of both security and operations. The CISO needs a plan to evaluate and manage the risk of cyber threat as it relates to IP. While your R&D chief is essential for determining exactly what IP needs looking after, the head of manufacturing knows where that property resides and the people involved with all aspects of the manufacturing processes. Your legal counsel will guide you about what and whom you’re allowed to monitor. Why HR? Someone needs to be a clearinghouse of information on all employees and to help coordinate intelligence sharing among the different departments.

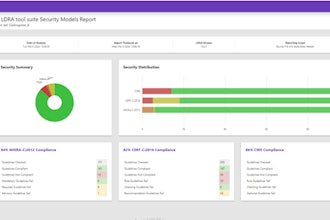

Second, assign risk levels to every job in your organization. Choose a scale of 1-10, with 10 as the highest risk, which corresponds to titles with the greatest access to critical, sensitive information. Or, use a system of Low, Medium, and High risk; Green, Yellow, and Red can serve the same function. The key thing is to have a current snapshot every employee’s role, as well as level of privileged access to pivotal information like IP. Clearly, the higher the risk, the greater the need to monitor someone in the organization.

Since I’ve introduced the subject of monitoring employees, let me break that into two very important ways to do so.

One is known as employee monitoring. This can pinpoint exactly when IP has been accessed—and what was done with it. The other is user and entity behavior analytics (UEBA), which sets a baseline of behavior for each employee and takes note of important variations or anomalies from that norm.

Employee monitoring provides a detailed video playback of activity before, during, and after someone taps into your IP. If a user, say, accesses a CAD drawing, takes a screenshot, copies and pastes it into a non-company e-mail account and sends it, employee monitoring can help determine the scope of the incident and the extent of the loss. It offers actionable intelligence for an immediate response.

UEBA algorithms alert an organization when an employee’s activities tied to his or her system credentials exceed the boundaries of normal use. Some systems also track users’ psycholinguistics, looking for aberrations from normal speech, tone, and word choices. These may indicate a shift in someone’s mood or thinking—key signs of depression or anger and early indications of a possible IP breach.

No safeguards are absolutely foolproof when it comes to IP theft by insiders. But having the right rapid-response team in place and assigning risk levels to all jobs and, therefore, which employees to monitor actively, is a start. Combining employee monitoring and UEBA can further head off disaster since one provides an early warning system for insiders who may be inclined to commit a nefarious act, the other an exact record of unusual activity or an actual breach.

Larry Thompson is President and CFO of Veriato, Inc.