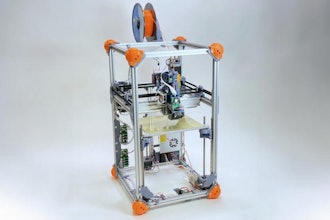

With the addition of 3D printing to a designer’s arsenal, prototyping becomes quicker and easier. Current 3D printers can quickly create models from multiple materials or from ultra-light plastic.

ZMorph CEO Przemek Jaworski and Guillermo Parodi, owner of Draw2CNC, both have their fingers on the pulse when it comes to what clients need from prototypes.

In his business, Jaworski saw that customers wanted the most available material, as well as the cheapest, such as ABS plastic. This allows for versatility and easy printing. ABS is a good material for prototyping not just because it is readily available, but also because it can be used for many different types of pieces.

PLA, a bioplastic based on corn, is also a popular material. There are a lot of possible setting techniques in order to refine the part after it is printed. Post-processing techniques including painting, smoothing, or sanding can change the appearance and strength of the part, making it smoother or rougher.

“Very often we can print parts with PLA and then use them as molds for other types of materials. The actual plastic part can be destroyed afterward,” Jaworski says. Alternatively, the original part in this situation can be used as a mold in order to create another version of the object with another material, such as ceramics.

3D printing and digital fabricating is useful for prototyping in other ways too. Objects larger than the surface area of the printer can be built by assembling parts together using acetone or adhesives.

(Image credit: Draw2CNC)

(Image credit: Draw2CNC)Acetone, which is used to smooth out or dissolve the crosshatched surfaces, can also make melted edges sticky, enabling different parts to be stuck together. Removing the part from the printer doesn’t necessarily have to be the last step, Jaworski says.

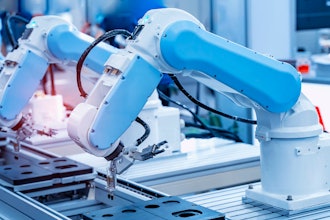

By combining 3D printing with subtractive techniques like CNC machining or laser cutting, there are even more possibilities. A part that is milled, for example, from aluminum can be combined with a printed part.

“You get a really, really strong part with some intricacies of geometry from the part that is 3D printed. So you can combine intricacy with strength,” Jaworski says.

Jaworski believes that one of the most underappreciated parts of creating a prototype through 3D printing is acquiring the 3D geometry. 3D models can be created by either the client or the printing company using 3D scanners. No matter what process one is using (CNC milling, 3D printing, or something else) creating reusable models can save time.

3D blueprints – probably made on one’s own in the case of prototyping but also possibly based on a plan from a manufacturer – are needed in order to make the part and be sure that its interior architecture can stand up to being printed. The prototype will then be able to accurately reflect the stresses that will be on the object when it enters the physical space.

Jaworski is always keeping an eye out for new materials. Conductive materials, which allow electrical signals to flow through them, might be the next big thing when it comes to printing prototypes that not only accurately show a potential product’s physical properties, but also its electrical properties. For example, Jaworski says, a company could produce a functioning robot in one piece.

“For now these conductive materials are of poor quality and very expensive, so it’s not happening yet, but it will happen at some point and things will change,” he says.

(Image credit: Draw2CNC)

(Image credit: Draw2CNC)His interest in the next generation of printers also focuses on the increased capabilities of desktop printers. The real key to making 3D printing more common is to find a “killer application” which no one yet uses 3D printing for, he says. That could enable people to print things at home and make printers an essential, common part of life more than ever before. Jaworski predicts that the key element of this change will not come from what materials are used, but from what they are used for.

Guillermo Parodi, owner of Draw2CNC, a CNC machining service, also weighs in on using CNC machines to create prototypes. Most of his clients request small aluminum parts, under 2 inches per side but with too much depth to produce on a router. Interest in Teflon parts is also on the rise.

Draw2CNC uses a free CAD program to let clients see how their product might be produced as a prototype using a CNC machine.

Parodi says that the most important thing to look for when considering using a CNC machine for prototyping is reliability. Especially for professional shops, a machine must be able to guarantee performance within the time reported to a client, and it must be able to meet expected yield.

Someone who wants to use a CNC machine for personal use might be less concerned about perfect reliability, but still needs to find a machine within the right price that will work as much and as efficiently as they need it to. Maximum volume must also be taken into consideration. Draw2CNC uses a minimum of 3-axis machines, but some companies may need the fourth axis depending on the type of work they do.

Both CNC machining and 3D printing, as well as a combination of both and additional subtractive techniques, have changed the way prototyping can be done in the modern era. The most important elements have not changed, though – a prototype must accurately reflect the finished product and be flexible and strong enough to undergo testing or display. Finding out what method will work best for your business is just the first step.