Most people might still consider the idea of using tides to generate electricity as outlandish as a trip to the moon. But starting this year, the concept is quickly becoming reality. “We went to the moon 46 years ago, and now we are using it to produce energy,” says Frederic Navarro, project director at GE Power Conversion in Belfort, France. “That’s because the moon’s gravity tugs on the ocean and produces predictable tides that run like clockwork, twice a day.”

Navarro leads a GE team that is helping build France’s first subsea tidal power plant for Electricité de France (EDF), near Paimpol-Brehat, in Brittany. When completed at the end of this year, it will generate 1 megawatt of renewable power and feed it through a 10-mile-long (16 kilometers) underwater cable to the local grid.

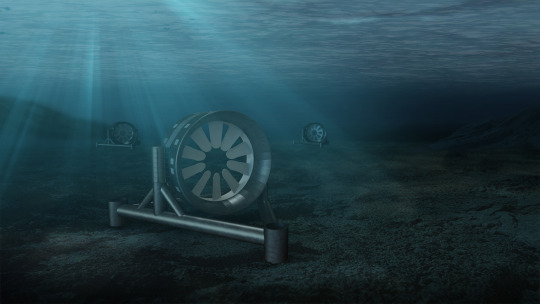

As the tides move in and out, they will spin two huge turbines measuring 16 meters in diameter and sitting 35 meters below the sea level. The turbines generate electricity with direct-drive permanent magnet generators and send it for processing to a subsea converter. Navarro calls it the “yellow submarine” because of the way it looks. “It works just like dropping a wind turbine to the bottom of the ocean and using water to move the blades,” says Navarro. “It’s that simple.”

The idea might be simple, but the execution takes some serious skills. The turbines, made by OpenHydro, a DCNS subsidiary specializing in the design, manufacture and installation of marine turbines, are so large they have to be assembled in a dry dock in the port of Brest and deployed using a custom built barge.

In the dock, they will be coupled with the “yellow submarine,” built by GE Power Conversion at GE Power & Water’s massive factory in Belfort. But it just happens that Belfort is the most geographically distant town from any coast in France. So last week, the company loaded the subsea vessel on a customized flatbed truck for the 650-mile long journey to Brest.

Navarro says the “yellow submarine,“ which is 9 meters long and 5 meters wide, will be “the brain” of the whole tidal array that decides how the turbine should move (see below). The technology inside will control the rotation of the turbines and optimize the power produced generators according to the speed of the tides. “There is a lot of complex engineering that takes place behind the yellow walls,” he says.

For example, it holds sophisticated technology that can independently control the speed of each turbine, transform their variable AC voltages to a high DC voltage, and reduce losses along the 16km subsea cable.

The current’s journey is anything but ordinary. When it first enters the “yellow submarine,” it travels through a chamber filled with nitrogen. “This allows us to remove any moisture and oxygen and prevent corrosion,” Navarro says.

The current then flows to an enclosure filled with special transformer oil. Made by Midel, the ester-based fluid has been custom-designed to protect the environment in case of a leak. “This stuff is more expensive than the best olive oil,” Navarro says.

Finally, the current travels to an onshore sub-station where another piece of GE technology transforms it again, so it can be connected to the French electrical grid.

DCNS and OpenHydro will assemble the turbines and the GE equipment in Brest and then tow them via barge to Paimpol-Brehat some 200 kilometers away.

That’s when some of the hardest work will begin. “Naturally, tidal arrays go to places where there are strong currents,” Navarro says. “But these currents also make such locations a tough place to work.”

OpenHydro will use specially trained divers to install the equipment some 35 meters below the surface. “The divers will be only able to work during certain times of the day, when the conditions aren’t dangerous,” Navarro says. The partners expect the array to start producing power by the end of the year.

France is far from being a tidal power newbie. In 1966, the country opened the world’s first tidal power station inside a bridge spanning the River Rance, in Brittany. Just like Paimpol-Brehat, the plant is currently operated by EDF.

Likewise, Paimpol-Brehat is not the only tidal project involving GE. In February, the company said it would supply technology for a massive, 320-megawatt tidal lagoon off the coast of Wales.

“Not too long ago, tidal power seemed like science fiction,” Navarro says. “But today, we’ve started unlocking the potential of tidal energy around the world.”