NORFOLK, Va. (AP) -- An idea that dates to Lewis and Clark's trek west is experiencing a rebirth thanks to the truck traffic that increasingly chokes highways: shift more of the nation's freight burden to boats that can traverse rivers, lakes, canals and coastal waters.

Increased concerns about fuel prices and global warming in recent years have revived interest in marine highways from the Erie Canal to the Chesapeake Bay to the coastal waters off Oregon, Massachusetts and Texas.

Proponents envision further expansion of the country's 25,000 miles of navigational waterways by making greater use of the coasts and inland routes, such as the St. Lawrence Seaway, the Great Lakes and the Mississippi and Ohio rivers.

A significant expansion of the marine highway system faces several obstacles:

-- Many locks haven't been updated in decades to accommodate increased freight traffic. Replacing the nation's lock system would cost an estimated $125 billion.

-- A harbor maintenance tax that can add $100 or more on an international cargo container shipped domestically by water. The tax is not collected on cargo moved by trucks or rail, or on U.S. exports.

-- The scarcity of U.S. ships to serve domestic ports along short-sea routes. Some blame a federal law that limits shipping between domestic ports to U.S.-built vessels whose crews are at least 75 percent American, a restriction intended to protect U.S. shipbuilders but which critics say has contributed to the industry's decline by stifling innovation.

Despite these infrastructure and regulatory constraints, entrepreneurs are charting a way forward, one tugboat trip at a time.

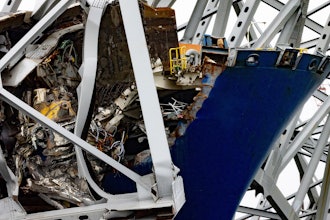

Ed Whitmore spent 11 years on Wall Street before returning to his native Virginia six years ago for the rough-and-tumble life of a tugboat operator. He took a "broken down, beat-up company" with one belching tug and grew Norfolk Tug Co. into a fleet of 10.

With the help of a $2.3 million federal grant, Norfolk Tug has made once-a-week runs up the James River since December 2008, delivering cargo from oceangoing vessels to the Port of Richmond. Each container loaded on a barge removes one truck from the 90-mile stretch along Interstate 64. Whitmore estimates his business removes roughly 4,000 trucks from I-64 each year.

"It's important to drive an initiative like this forward," said Whitmore, whose French cuffs hark to his days in structured finance.

The "64 Express" already has captured a tiny piece of packaging maker MeadWestvaco Corp.'s huge shipping portfolio. Large rolls of paper from its Covington mill in far western Virginia are trucked to the Port of Richmond and Whitmore's barges for export from the coast.

Lawmakers from coastal states and along likely inland routes such as the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes favor short-sea shipping as a means to economic development and job creation.

"In a day and age when we're trying to save energy and reduce pollution and we're trying to take some of the clutter off our highways, it just makes sense to do it," said Rep. Elijah E. Cummings, D-Md.

The rail and trucking industries don't pay much mind to their much smaller shipping counterpart, though they don't want to see it grow as a result of public policy. "The market should govern how short-sea shipping is used," said Clayton W. Boyce, a spokesman for American Trucking Associations.

Before the development of a national rail system and later an interstate highway system, nearly all the country's goods were shipped on boats. Today, 94 percent of all domestic freight moves on rail or by truck. But not without some cost.

Congestion on roads and rails costs the U.S. economy as much as $200 billion annually and 44 billion person hours, according to the Transportation Department.

One 15-barge tow removes 1,050 tractor-trailers from the highways. And with just a gallon of diesel, a barge can move one ton of cargo 576 miles. A rail car using the same amount of fuel moves that ton of cargo 413 miles, while a truck gets only 155 miles.

Short-sea shipping advocates also point to a strong safety and environmental record.

In 2005 and 2006, spill rates were 6 gallons per 1 million ton-miles for trucks, 3.86 gallons for rail, and 3.6 gallons for barges, according to a Texas Transportation Institute study conducted for federal transportation officials.

When accidents do occur on water, the impact tends to be large. In July, a tug on the Mississippi near New Orleans veered into the path of a tanker, causing a rupture that spilled 283,000 gallons of oil and shut the waterway for days.

The economic stimulus package passed by Congress included $27 billion for road-building projects and $12 billion for rail and other infrastructure improvements -- but not a nickel was specifically directed at short-sea shipping.

Proponents of funding for marine highways, including the chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, Rep. James Oberstar, D-Minn., say their next best opportunity will be the debate on the fiscal 2010 federal budget.

For the time being, Chris Osen, vice president of supply management for MeadWestvaco, said his company's commitment to short-sea shipping is based on pragmatism, with an undercurrent of idealism.

"Everything we do has to be the most cost advantageous to us," he said. The company will select a "green route, if all things are equal."