SEATTLE (AP) -- On picket lines in Seattle and production lines in Pittsburgh, union workers are showing no fear in demanding a hefty chunk of the profits from Boeing Co. and United States Steel Corp., whose businesses have soared above the more widespread economic downdrafts in other sectors.

On Tuesday the United Steelworkers union ratified a four-year contract their chief negotiator, Tom Conway, touted as the best in the nation's steel industry in 30 years. The deal provides a $6,000 cash payment, a retroactive $1 an hour pay increase to Sept. 1, and 4 percent wage increases in each of the next three years, among other things.

And on Saturday the Machinists union shut down Boeing's lucrative aircraft assembly plants after rejecting a 3-year contract offer containing bonuses averaging $6,400, pay raises averaging 11 percent, pension increases and a 3 percent cost-of-living adjustment -- $34,000 in average pay and benefit gains, by company estimates.

Moreover, the strike vote was a whopping 87 percent, compared with a 78 percent strike vote that preceded a 69-day walkout at Boeing in 1995, when the Machinists represented even more workers at the company.

Financial analysts and some within labor's ranks question whether demands for more money across the board and stronger job security are reasonable or realistic, but Tom Buffenbarger, president of the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, and chief negotiator Mark Blondin say Boeing can well afford it.

Boeing reported $4.1 billion in profit last year, an 84 percent increase over 2006, and has about a seven-year order backlog, helped by strong exports.

A good deal for the Machinists -- financially and in outsource-limiting provisions -- will promote a rising tide to float other labor boats, Blondin and Buffenbarger said.

"It raises the bar in the community," Blondin said. It's going to help everybody in this community, if not the country."

He said he hears plenty from other labor leaders about the rich deal the Machinists already have at Boeing, making an average of $27 an hour or about $56,000 a year before overtime and incentives, but added that in the strike "I've had nothing but encouragement from other unions."

Gains at Boeing may even "bleed over into to airlines," where the Machinists have been hard hit by mergers and the fiscal pinch of soaring fuel costs, Buffenbarger said. "Maybe there's hope yet for our workers in the airline industry."

Unlike the vast majority of U.S. unions, the Machinists hold a heavy hammer at Boeing. Because of the wide range of highly skilled and specialized positions they fill, the company cannot make airplanes without them or find enough available and qualified replacements -- especially in the Puget Sound area, where the assembly plants are concentrated.

Chicago-based Boeing also is an anomaly, one of two manufacturers of large commercial passenger and cargo jets in the world. Its European competitor, Airbus S.A.S., also has a long order backlog and powerful, bellicose unions.

"This is America's last successful major heavy industry," said Richard Aboulafia, vice president and analyst for the Teal Group in Fairfax, Va. "As a result, the workers have a lot more power ... and they're taking advantage of that power."

Still, last year, 12.1 percent of U.S. workers belonged to a union and 13.3 percent were covered by union contracts, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. In the private sector the figures for 2007 were 7.5 percent members and 8.2 percent represented.

Peter Morici, an international business professor at the Robert H. Smith School of Business at the University of Maryland, said there was little likelihood the actions of the Machinists would carry over to affect inflation or other economics trends.

"I don't think it will influence enough of the economy to mean anything," Morici said.

Morici agreed that Boeing's outlook for now is strong but said the Machinists can push their case only so far and for so long.

"This is a good example of why manufacturing is leaving the country," Morici said. "This is like the UAW (United Auto Workers) in the '50s."

Meanwhile, the United Steelworkers have also bargained hard and won a contract with United States Steel that impressed experts.

Charles Bradford, an analyst with Bradford Research/Soleil Securities, said: "On a very basic level, the company's making a lot of money. The employees have gotten very good profit sharing and bonuses."

Gary Chaison, a labor specialist at Clark University in Worcester, Mass., said the agreement was "excellent" because it included positive pay increases rather than the cuts or freezes that have characterized past contracts in the U.S. steel industry, which has been declining since the 1980s.

"That's an agreement that the union could be proud of," he said of the USW contract.

Still, Boeing and the Machinists know how fast leverage can fade.

The number of workers represented by the union fell to about 18,400 in 2005, four years after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. A 24-day strike in 2005 was settled with an agreement that left health care premiums untouched and provided cash payments totaling $11,000 over three years but no general wage increases.

Now the Machinists' contract covers 27,000 at Boeing.

Buffenbarger, speaking from the Machinists' convention in Orlando, Fla., said the prickliest issue in the strike is job security because -- unlike pensions or health care or wage scales or other equally critical issues -- it cuts across all age groups, pay grades, experience range and other groups within the work force.

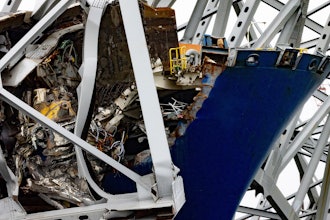

The issue has grown more heated for the union as Boeing has taken an unprecedented approach in making its next-generation 787 jet. From the start, Boeing planned to have outside companies make most of the components, including such key parts as the wing.

The company makes 30 percent of the plane's parts and buys the remaining 70 percent from outside suppliers spanning the globe, from Japan to the U.S. The parts breakdown for other Boeing planes is comparable, though it was closer to 50-50 earlier this decade, according to the company.

Job security "keeps climbing the ladder of importance in the surveys that we have done of our membership," Buffenbarger said. "this is the time to secure the future...

"Somebody's got to break the mold of this outsourcing."

AP Business Writer Daniel Lovering in Pittsburg contributed to this report.