WHITE HALL, Ark. (AP) -- During the Cold War, the Pine Bluff Arsenal held the secrets of the nation's stockpile chemical and biological weapons against prying Soviet eyes. Now, arsenal commander Col. Bill Barnett worries about disclosing how many gas masks and mortar rounds workers can produce in a day.

The fear comes not from the threat of foreign spies, but rather the possibility of being undercut by competing private manufacturers.

"We are a business," the former Special Forces warrior said. "It's a very unique environment."

As the arsenal prepares to eliminate its remaining mustard gas, the base about 35 miles southeast of Little Rock finds its mission changing as the United States destroys the weapons it and other eight other arsenal sites once housed. While some only housed the biological and chemical agents, other bases now manufacture weapons or other items needed as the nation fights two other wars abroad.

The Pine Bluff Arsenal, conceived a month before the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, had the task of building grenades and bombs for the growing U.S. military. Over time, the arsenal began manufacturing chemical and biological weapons, storing them in earthen igloos that also housed German rockets studied after World War II.

In 1997, the U.S. signed an international treaty pledging to eliminate its chemical weapons stockpiles. The Army and private contractors face a 2017 deadline set by Congress to eliminate the weapons.

The Army has destroyed two stockpiles -- the Johnston Atoll depot 800 miles southwest of Hawaii and the weapons once stored at Maryland's Aberdeen Proving Ground. Depots holding the weapons in Colorado, Indiana, Oregon and Utah will "go away" when destruction operations end, said Greg Mahall, a spokesman for the Army's Chemical Materials Agency.

"Once that's done, we as the Army should be vacating those premises and sending them back for uses yet to be determined but outside of the Army's purview," Mahall said.

The remaining bases have other specialties. In Anniston, Ala., workers on the Army base also overhaul combat vehicles and recycle missiles. Kentucky's Blue Grass Army Depot stores conventional ammunition and handles other maintenance operations.

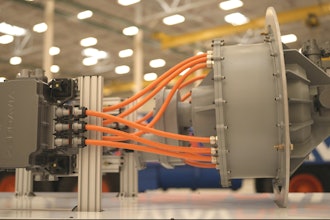

In Pine Bluff, the 13,000-acre arsenal that once housed some of the Army's deadliest weapons now manufactures nonlethal ordnance. Mortars built along the arsenal's assembly lines provide high-intensity or infrared light for soldiers at night. Across the base, other workers put together green rubber gas masks, funneling smoky air through them to test them for leaks.

Barnett, an Army ranger who served in the desert during the Persian Gulf war, said he likely used some of the smoke rounds made at the Pine Bluff Arsenal during the war. However, he said he would have no qualms turning the base's manufacturing operations back to building lethal rounds.

"If there was a need for it, we'd make a round," Barnett said. "We're obviously always out there looking to expand the market if we can do that."

The arsenal also refurbishes and maintains shelters and equipment used to decontaminate people and equipment after an attack with chemical or biological weapons. The Food and Drug Administration's National Center for Toxicological Research, a separate operation, sits next to the arsenal in the neighboring town of Jefferson.

All those factors make the arsenal a promising site for future projects, Barnett said. About 2,500 people work at the base, including the contractors destroying the base's chemical weapons. While many of those destroying the weapons likely will leave the area after cleanup operations end in the coming years, the colonel said he wants to attract other work for the arsenal's production lines.

Demand for the arsenal's ordnance continues at a strong pace, as soldiers will continue their deployment for the near future in Afghanistan and Iraq. At a manufacturing line making infrared mortars, workers screw together and attach fins to the 30-pound rounds.

The rounds drop into metal containers and workers use a hydraulic lift to place them onto pallets. Each round bears a serial number starting with the letters "PB."

"To me, it's like my signature, his signature, her signature -- we take a lot of pride in that," said Roch Byrne, director of ammunition operations at the arsenal. "Soldiers deserve the very best and that's what they're getting from us."