As the economy has turned around and employers have been seeking to invest in fresh blood, a consistent tone of unemployable youth has been ringing from the manufacturing and engineering ranks. The skills gap is a growing problem as baby boomers are retiring and green workers are attempting to enter the workforce.

As the economy has turned around and employers have been seeking to invest in fresh blood, a consistent tone of unemployable youth has been ringing from the manufacturing and engineering ranks. The skills gap is a growing problem as baby boomers are retiring and green workers are attempting to enter the workforce.

Read: What Happens When The Boomers Retire?

The need for new blood has led to new STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) initiatives and apprenticeship programs from our government, as well as major corporations.

According to a recent article in The Atlantic, Germany has continued to invest in developing these programs, and has succeeded in matching young workers to valuable positions in the workforce.

This is all well and good, but I have an instant, unnerving feeling about major investment in apprenticeship programs. While the programs may have some merit, I put weight in what the New York Times reports, “What employers describe as talent shortages are often failures to agree on salary.”

The issue here is less about properly trained prospective employees, and more about employers shying away from investment in new talent (whether it’s by choice or by fiscal force).

Reshoring initiatives have done a lot of good to bring regional manufacturing jobs back to the U.S., but those companies still have to compete (even if their competition still pays pennies for labor). Many manufacturing workers of old were happy to work at wages upwards of $20 to $25 an hour, or more – fitting pay for a hard day’s work. Incoming workers, educated or not, can easily use the internet to give them insight into their predecessor’s pay.

The landscape of the manufacturing industry has changed drastically over the last five years, let alone the last 25 to 30 years (when the retiring baby boomers were first employed). When adjusted for inflation, wages have gotten lower (starting wages are even lower than that), and companies still have a broad field of prospecting candidates for jobs.

When more fish are in the sea of prospective employees, a company can be painfully explicit on position requirements. A couple decades ago, employers were willing to train anybody with a solid work ethic.

I find two issues in this conundrum. First, employers with tunnel vision can cause a falsified skills gap. In the current environment, employers tend to want newcomers to already know the job and be ready to work. Only if a potential employee – with swami-like insight, a sway of dumb luck, or an obscure interest – has focused training in a niche area, can he or she be considered employable by some companies.

The other issue is the false idea that industry-specific training is only required for those who want to move up within a specific company or within a certain skillset, when in fact training and education beyond the basics is almost a requirement for employment these days. The uneducated and untrained have almost no hope of employability, but to that end, neither do those who are trained in the ‘wrong’ area or industry.

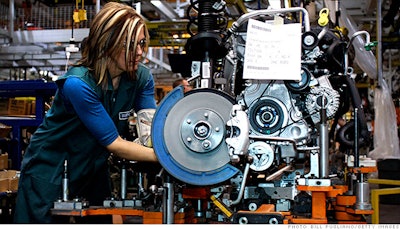

My father is a retired GM plant worker, and he always joked about the specifics of his position: “Putting a blue peg in a blue hole.” In our time, assembly line workers can no longer rely on the ability to articulate a color-coordinated, peg-hole combination. They need to know how the production machines operate, as well as the products they are helping to manufacture, sometimes even understanding quality control, ERP, supply chain management, lean manufacturing principles, etc. – and this is at the entry level.

The Atlantic may be right, we may need to take a cue from Germany when it comes to initiating apprenticeship programs, but that alone will not put an end to the ever-growing skills gap.

Is a better apprenticeship infrastructure the answer to a more employable workforce? What is the best way to find qualified new employees without breaking the bank? Comment below or email [email protected].