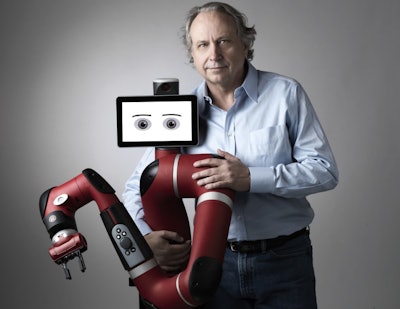

Rodney Brooks, founder of Rethink Robotics, introduced the concept of cost-effective and collaborative robotics in manufacturing with Baxter and Sawyer. In the last installment of this two-part Q&A with Brooks, he explains why robots need to have facial expressions and what it will take for robots to finally have “good robot hands.”

What kind of tasks are most difficult for robots that humans can do easily?

The tricky part is where there is dexterity involved, our robots are no good at it. We can only have robots do the repetitive stuff that isn’t really dexterous at the moment, because they don’t have really good robot hands. We haven’t invented them yet – not even in labs.

Human hands are amazing things, and it’s not something in which robotics have been able to make much progress. People have worked on it for over 40 years, but we haven’t done very well.

What will it take to make strides with dexterous robots?

First, it requires better mechanical design. Second, it requires better sensors embedded in the system — very small, multiple sensors with a sense of touch.

Third, in our human hands, the material properties of the skin are very important. Fourth, we need new materials for robot hands, and we need algorithms to combine those four things, which are very difficult technical fields.

When I talk to government funding agencies, I say, “This is something you should try and fund: these teams of people working on these four things together.”

Until then, I don’t think we’ll make progress on dexterous hands. It’s so far away from commercial reality.

What factors do you consider when developing the look of a robot?

Anything about the appearance of a robot is making a promise of what it is, and it better deliver on that promise.

I’ve seen people build robots that look like Albert Einstein. That’s sort of making a promise about how smart they are, and they can’t possibly deliver on that promise. So you should design it in such a way that the promise it’s making is what it delivers, so that people are not weirded out by it. You don’t want to be promising something you’re not delivering, because people will soon be cynical about it.

Are there surprising factors that robot designers and engineers consider when it comes to improving worker-robot collaboration?

I think people misunderstand why there are facial expressions on Baxter and Sawyer. It’s not necessarily about being friendlier. When both robots are about to reach somewhere, on the screen their animated eyes glance where they’re about to reach.

People do that all the time. You pick up on the cue of where a person’s eyes are looking for what they’re about to do next. That’s what we try to do with the robots. We have them do the same sort of thing a person does, and people pick that up. They’re not surprised when the robot moves, because the robot looked first before it moved its arm. That’s an unconscious cue that we’re just used to.

That’s one of the problems with a fully self-driving car without a person in it. When you’re crossing a busy street and you see a car coming, you look and see what the driver is doing inside the car. If they’re on the cell phone looking the other way, you don’t step out in front of the car. But if they look at you and make eye contact and nod or wave their hand, you know that they’re not planning, unless they’re a psychopath, to drive over you. You have social interaction with that driver.

(Image credit: Rethink Robotics via GE Reports)

(Image credit: Rethink Robotics via GE Reports)Where are the biggest opportunities in robotics? Are there disruptive innovations coming in the field that will catch people by surprise?

A surprise I’ve seen in technology over the last three years is how much better speech understanding systems have gotten. Not that many years ago, our speech understanding systems were to press or say “two” on a phone for frustration. You couldn’t even get a phone to understand the number two.

Now we have speech understanding on Siri or Alexa. I used my Amazon Echo last night and said, “Alexa, play some classical music for me,” and it just works. I was 30 feet away at one point, and I wanted to switch it up. I said, “Alexa, stop.” And it heard me from 30 feet away. That was unimaginable I think three or four years ago. Deep learning has helped those speech understanding systems immeasurably.

The thing that’s about to develop more and surprise people is using that same deep learning technique for certain aspects of computer vision. Our robots and systems will see things better than they have in the past with cameras and understand what’s in the image. It won’t be anywhere near as good as a person, but it will be way better than what we’ve had. And that will start to be applied in factories and automation — maybe ultimately in the home.

We’ve seen great technological strides with smartphones, communications, networks and speech understanding systems, but if you look inside our factories or China’s factories, what you see is very old technology with a tremendous installed based. So you can’t just wipe it clean and start again, nor would you want to. But I think there are tremendous opportunities for factories in the same way digital has taken our entertainment and our communications.

We’re only just beginning that journey because of that incredibly large installed base of old technologies. You can’t replace it directly, so the challenge is: How do you, bottom up, put little pieces in and improve it over time and lead to more digital?

Rodney Brooks is founder, chairman and CTO of Rethink Robotics and co-founder of iRobot.