The light filters inside St. John’s Episcopal Church in Franklin, Pa., through a set of precious Tiffany windows framing its spacious nave. This life-size kaleidoscope of colors harkens back to a time over a century ago, when Franklin was at the epicenter of America’s first oil boom.

The good times didn’t last.

The wells stopped producing and local energy companies like Pennzoil, Quaker State and Wolf’s Head decamped for Texas and elsewhere by the mid 1980s. “The good-paying jobs went with them and the county became economically depressed,” says John Dumot, president and CEO of Liberty Electronics. “We had to reinvent ourselves.”

Franklin’s rebirth is an unlikely success story. The local community pooled money to start businesses like Liberty, which makes wiring harnesses, cable assemblies and other electrical products for the military but also large customers like GE and Westinghouse. The company, which started in 1985 with $600,000 in financing and 50 workers, now employs 340 people and pulled in $36 million in 2014 revenues. But once again, that prosperity is in danger.

Liberty’s products ride the rails inside GE locomotives built for customers based in Egypt, Kazakhstan, Indonesia and elsewhere. In fact, GE makes up roughly one-third of Liberty’s business.

But many of these international sales were secured by the Export-Import Bank, America’s export credit agency that provides loan guarantees and helps customers abroad purchase U.S. products. There’s a movement afoot in Congress to shut it down, and many small and mid-sized businesses like Liberty are worried. “I have a conservative bent, support small government and less regulation, but this seems like a crazy place to start,” says Scott Anderson, vice president of operations at Liberty. “This bank is producing a net return. I don’t understand why they are even looking at it. Other countries have it and it helps us level the playing field.”

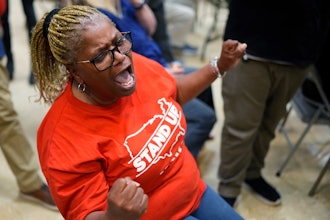

Scott is in Washington, D.C., today to attend the Ex-Im Fly-In, a large gathering of some 900 U.S. exporters seeking to re-authorize and secure the Ex-Im bank’s charter, which is set to expire at the end of June. “I saw the stories in the paper and, at first, didn’t grasp the impact,” Liberty CEO Dumont says. “But then I realized that the shut down would hit us. Without Ex-Im, GE would struggle to sell abroad and we would lose that revenue.”

The Ex-Im Coalition, which represents thousands of big and small American manufacturers and chambers of commerce, estimates that the bank supported 1.3 million U.S. jobs in the last six years, and had a positive effect on the entire American manufacturing sector, which employs 17 million people.

Back in 1985, Liberty started with 50 shareholders, mostly from Franklin and the surrounding the area. The number has grown since, and now more than 80 locals hold a stake in the company, not to mention jobs. “We are an anchor for the community,” Dumot says. “If we close Ex-Im, we could lose as much as a fifth or more of our business. This could backfire on everyone.”

For more stories like this, check out GE Reports.