Move over Tony Stark — this half pint has gone from a 2D viral video sensation to become a 3D marketing phenomenon.

Anaheim, CA-based Action Prototype and Urethane Castings (APUC) is a division of Action Mold & Tool (AMT) that provides comprehensive rapid prototyping and manufacturing services designed to quickly and efficiently bring new products to market. AMT is a custom injection molding company that was founded in 1993 by current owner Bill Hall. Six years ago, Hall partnered with industry veteran Chris Wentworth to bring prototyping and urethane casting under the AMT to perform small volume runs for clients.

Before APUC, Wentworth spent 10 years working in electronic assembly before he jumped into rapid prototyping. Admittedly, he made the jump to 3D because the new work was "much cooler." Wentworth grabbed a firm hold of the upstart industry when he went to work for American Precision Prototyping (APP) as the general manager of the company’s west coast division. He had more than three years at APP when the company uprooted and pulled back to Oklahoma. Wentworth was laid off and Hall was looking to make AMT a one-stop engineering shop for clients.

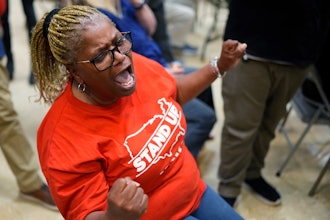

Two years later, the partnership is flourishing and AMT is growing. Much of the growth can be credited to strong word of mouth and client retention, but a big part of the marketing game relies on booth space at industry conventions. As engineers, managers, and owners walked the aisles of MD&M West 2012, APUC’s booth had an eye-catching draw. What first appeared to be a 12" scale, 3D-printed model of Marvel’s Iron Man was, upon further inspection, a bit too pudgy to be an exact replica — oh yeah, and it appeared to be wearing a diaper under that high-tech exoskeleton.

‘Trust Me, It’s Printable’

In 2010, independent director Patrick Boivin partnered with friend and CG artist STROB to take a blockbuster movie, replace the main character with a baby (Boivin’s daughter Margaret), and create a viral video sensation. After two months of production, Iron Baby was an immediate internet success and has since tallied more than 12 million views on YouTube.

STROB had created the zero thickness model in 3D Studio Max and, after the video was a hit, he approached multiple additive manufacturing service bureaus to have a solid model created from his file. After multiple firms told him it couldn’t be done, STROB was approached by Wentworth, who just so happened to excel at manipulating data to create a solid and printable file.

"A lot of what I do, I can’t show," says Wentworth. The aerospace, automotive, medical, and consumer electronics industries make up 90% of APUC’s business and much of his work comes with non-disclosure agreements. The work is rewarding (making a difference, etc.), but he is unable to showcase his abilities.

"I look for projects that can display my skill," he says. "I saw the Iron Baby video, emailed the video creator, and asked him if he ever considered printing out his Iron Baby." When it came to Iron Man, or Baby, Wentworth knew he was capable, as he had narrowly missed out on the contract to work on the actual Iron Man movie. The contract was awarded to Solid Concepts which, according to Wentworth, won because the company is located down the street from special effects house Legacy Effects (formerly Stan Winston Studios).

When STROB replied he was hesitant. After all, he had been denied by a number of other companies, but Wentworth was confident. "Trust me," he replied. "It’s printable, send me the data."

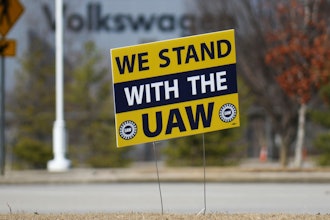

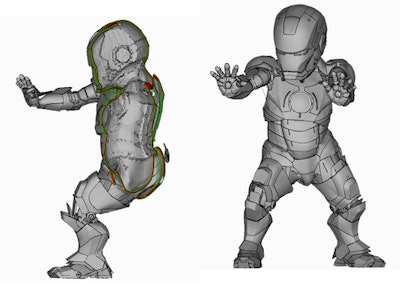

To make the data printable, Chris Wentworth had to give each of the zero thickness faces, as seen on the right, girth (left).

Raw Data

To make the data printable, Wentworth had to give each of the zero thickness faces girth. He wanted to make the file a solid mass and then hollow it out.

At first, he brought it into his CAD software to thicken it. According to Wentworth, he used five different CAD programs, including Rhino and netfabb Studio Professional, to "massage the data."

"I don’t like to say what [all five CAD programs] are because then engineers will know how I do it, and I’ll be useless," Wentworth shares regarding his coveted secret formula.

Given the meticulous nature of the model, Wentworth slaved over the model thickness for months on end. Well, not exactly. The entire process took him less than a day. "The model was 90% complete," he says. "Everything on the exterior was there, I just had to add the inside and massage the data to get the model to where it needed to be."

To massage the data, Wentworth first deleted and merged anything that wouldn’t be seen on the exterior. For example, the outside of the fingers were hollow shells and the insides were solid. He merged the data to make both parts one solid piece and deleted any remaining artifacts. He went through Iron Baby piece by piece.

"In [3D Studio Max], all you see is the outfacing surface, you don’t need the in-facing surface," Wentworth says. "A lot of CAD guys who work on movies or games aren’t going to make the data complete, they only need the outside surface. I had to make each plate solid by closing it off or giving it thickness. Once I had the many shells solid, I merged them; hollowed the file; and sent it to the printer."

Print Baby, Print

STROB’s creation was printed on 3D Systems’ iPro 8000 SLA production printer, a mid-size, high throughput system that builds parts with surface smoothness, feature resolution, edge definition, and tolerances that rival CNC-machined parts, according to the company. Each Iron Baby was printed in eight to 10 hours and had to be printed in two halves, due to the size of the iPro build envelope.

Wentworth opted to print her in Accura 60, a hard, clear plastic with the aesthetics of molded polycarbonate, so that he could add LEDs to the design in order to illuminate the eyes, palms, and arc reactor (chest). Before he added the LEDs, Wentworth filled the SLA with clear urethane and then drilled holes to be able to install the light source. In hindsight, he may have done things differently. "If I was was thinking ahead, I would’ve put the lights in first and then filled it with urethane, but I was afraid of the lights twisting," he recalls. "If your LED is off just a little, you won’t get light where you want it."

The finishing process was simple. After an initial sanding, Wentworth used Bondo body filler to smooth out the layers. He then hit it with a layer of spray paint primer before sanding it again. "I had to sand out all of the layer lines," he says. "I used Bondo because the printed layers are four microns thick and I had to smooth out the layers in between." According to Wentworth, the process help prevent visible ridges and layers.

Throughout the entire process, Wentworth only went through two file iterations. On the first 8" print, some areas were too thin and some of the plates were not completely joined, causing them to pop apart. Some of the finger detail wasn’t thickened, so the initial print was missing a few digits. All Wentworth had to do was go back into the original file to thicken and tweak a few areas.

"The first part is typically the guinea pig," he says. "Some of the parts looked good in the computer, but came out too thin. If you look at it in the computer, it doesn’t come out exactly the same, so I went in and thickened some parts that were too thin. On the second print it came out really well." He even upped the scale (12") for the second print, but the issues had been resolved.

Wentworth admits that Iron Baby is more of a show piece than a feat of engineering, but sometimes it takes an eye-popping oddity (or at least a curiosity) to steer potential clients to a company’s core competencies.

"We made it to show people what we can do with SLA," he says. "What I did wasn’t really complicated. A lot of CAD guys that are fresh out of school wouldn’t be able to do it, but I have 15 years of experience working on getting parts made on machines, by either subtractive or additive means."

He may be modest about the success of the project, but after STROB and Boivin received their figurines, they were so excited that they purchased three more. It turns out that Iron Man director Jon Favreau was such a fan of the viral video that Marvel Comics invited STROB out to its New York City headquarters. During his visit, he presented Iron Baby figurines to Favreau and two other principle members of Marvel Comics. No word on the Iron Baby movie deal yet — Margaret must be tied up with other projects.